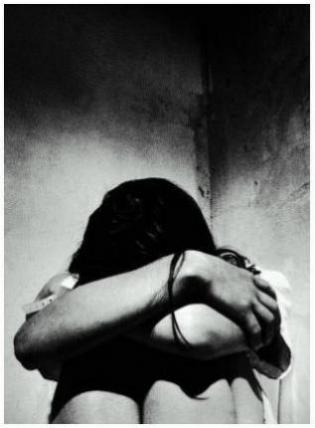

“Some days I just wanted to crawl into a closet and scream… ”

“Some days I just wanted to crawl into a closet and scream… ”

“One morning I found I simply could not get out of bed. The simple action of pushing back the sheet was too hard. I had nothing left…”

“My mother’s brain is gone, but her body is like the energizer bunny. Keeps on going and going and going … and I can’t keep up. I’m so tired I am getting sick all the time…”

“Dad keeps sneaking out. How can someone who remembers nothing be so clever … he’s an escape artist…”

For the millions of caregivers tackling the challenge of caring for someone with Dementia, most commonly in the form of Alzheimer’s disease affecting a parent, spouse or sibling, things like exhaustion, stress, declining health (their own), anger, rage, guilt and other emotions and issues are “normal.” It’s what happens when otherwise healthy people are suddenly confronted with the 24/7 reality of care-giving. A kind of care-giving measured not in days, weeks, or months, but years.

As Alzheimer’s reaches near epidemic proportions and is affecting ever increasing millions of people who are living longer (if not always better), and the pool of available caregivers shrinks, the pressures are mounting. And caregivers are crumbling under the weight of their complex responsibilities.

At one time caregivers were told were told “it’s all in your head” when they complained of fatigue, and all these other mental and physical issues. That great multipurpose line implied that not being a person of superpowers and extraordinary coping skills was a reflection on one’s competence in dealing with life.

The professionals were wrong. It’s not “in your head.” It’s real, and it has a name: Caregiver Syndrome, the technical name now being applied to the basic stresses on body, mind and spirit that care-giving for someone with Dementia can cause.

The professionals were wrong. It’s not “in your head.” It’s real, and it has a name: Caregiver Syndrome, the technical name now being applied to the basic stresses on body, mind and spirit that care-giving for someone with Dementia can cause.

Dr. Jean Posner, a Baltimore neurologist, who has studied the syndrome and the symptoms, calls it “a debilitating condition” triggered by “unrelieved, constant care” of someone with dementia or other chronic illness.

Only a decade ago, when the realities of the AD explosion became a visible, talked about and increasingly debated growing reality did health administrators, doctors and government officials start taking a good look at who is going to care, not only for the patients, but the caregivers. And how will that be accomplished?

The statistics are intimidating: one in every four families now cares for someone over the age of 50. In 2000, some 35 million Americans were over 65; that number, augmented by the post World War II bubble of baby-boomers, will hit 71 million — double — by 2030. The numbers are staggering and threaten to collapse the system of medical and elder care.

Caregivers, those unpaid, committed souls working from a sense of love and responsibility on the frontlines of home health care, are most commonly affected by depression, anxiety and anger. But these emotional stresses also translate into physical conditions of high blood pressure, diabetes and deteriorating immune systems and even progressive memory loss — mimicking the symptoms of those they care for. The older the caregiver, the higher the risks, and some it is now documented that over 60% of caregivers will experience at least some combination of these symptoms. Prolonged and elevated levels of stress hormones are triggered by prolonged care-giving, which usually dovetails with self-neglect. Caregivers are so busy caring for someone, they fail to care for themselves. Caregiver stress can be the match of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

It’s not just the physical care-giving; watching the decline and the certainty of the progression of dementing illnesses is literally watching someone die. Not a single age-related death but a lengthy decline that may last for years, accompanied by an ongoing sense of loss triggered in small increments: one function, one memory at a time evaporates. Each one constitutes a loss. And the losses are relentless.

After not just months but years of coping with these periodic losses, after this “staging down” or chronic deterioration has drained the caregivers and left their charges little more than shells of their former selves, after a thousand small deaths within the human brain, these caregivers are KO’ed by the reality of physical death. In the aftermath of a death from Dementia, the caregivers collapse. Some are relieved, but too many are simply unable to reclaim the time, energy and vitality expended in the relative isolation of multi-year care-giving.

Caregiver Syndrome is acknowledged among providers of care to the terminally ill — and make no mistake, Dementias are terminal illnesses — but it has yet to be acknowledged in American medical training and literature. So doctors miss it.

Many years ago, families took care of each and their aging and infirm relatives. it was simply the way things were handled. Nursing homes and assisted living sites were anomalies.

In the high pitched rapid fire pace of 21st century lifestyles, less value is placed on the efforts of care-giving, and the attached responsibilities are more often seen as ongoing burdens. Our society simply does not place adequate value on its elders or the people who care for them, creating an isolation and lack of peripheral and direct supports that affect many who give care. These unsung heroes become shadows figures in a world that is passing them by.

The American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Center for Care-giving are lobbying for the implementation of stress and depression screening for all caregivers, and urging those who feel overwhelmed by the pressures of giving care to speak candidly with their physicians (and social workers, if such professionals are involved in a dementia case). Respite time, social supports and improved training in care-giving and coping skills may go a long way to relieving the impact of care-giving on the human body and its overstressed mind.

The American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Center for Care-giving are lobbying for the implementation of stress and depression screening for all caregivers, and urging those who feel overwhelmed by the pressures of giving care to speak candidly with their physicians (and social workers, if such professionals are involved in a dementia case). Respite time, social supports and improved training in care-giving and coping skills may go a long way to relieving the impact of care-giving on the human body and its overstressed mind.

Caregivers often feel as if they are going crazy. They are not. And now there is a name attached to what they feel. Caregiver Syndrome. It’s not just all in their heads.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Editor’s Note: Local Councils on Aging, the National Alzheimer’s Association, local hospitals, mental health agencies and senior service providers all offer assistance and information at varying levels to caregivers in need of assistance. One phone call can make a difference in the quality of life for both the caregiver and the person being cared for.

If you need information on Alzheimer’s Disease or how to provide care for someone with Dementia in any of its forms, call the National Alzheimer’s Association 24-hour hotline at 1-800-272-3900.

The U.S. Administration on Aging also offers an Eldercare Locater Service. Call 1-800-677-1116 Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. eastern Standard Time.

Caregiver syndrome doesn’t just affect those caring for dementia or terminally ill patients — burnout can happen for anyone caring for a parent, spouse or child with a long-term illness. The guilt over taking a few minutes for yourself can be overwhelming, but it’s important for caregivers to give themselves a break every day, even it just means wandering through the grocery store alone, or sitting outside by yourself for a few minutes.