Clarksville, TN – Our lives here in Middle Tennessee are built upon the foundation of those who lived before us. The names of these souls of long ago are sprinkled upon our consciousness as they are now reflected in the names of our counties, cities, and roads: John Montgomery, George Rogers Clark, James Robertson, etc.

Clarksville, TN – Our lives here in Middle Tennessee are built upon the foundation of those who lived before us. The names of these souls of long ago are sprinkled upon our consciousness as they are now reflected in the names of our counties, cities, and roads: John Montgomery, George Rogers Clark, James Robertson, etc.

They are people who lived the prime of their lives in the late 18th century on the cusp of a new nation, bordering a frontier with a plethora of possibilities. These men are revered and their lives have been boiled down to a thick consistency of stories that all reflect their heroism, bravery, and sometimes larger than life achievements.

In the past there has been a definite vibe that they are only to be portrayed as one dimensional hero type characters and to do otherwise would be akin to blasphemy.

Both of these personas were later romanticized for their apparent adventure and nobility. At the end of their lives many of these men and their families were participants in westward expansion as frontiersmen and Indian fighters.

What has become lost is the other side of the story: their mistakes and where it seems they failed humanity. The stories of their lives should be revisited and hopefully remembered realistically and in balance.

Our culture and history are no different than most, in that for generations the idea of warfare has been celebrated. The tales of Indian fighters and revolutionary war heroes were no doubt shared with great enthusiasm at many a dinner table well into the 19th century.

In the last couple of decades great strides have been made in balancing out the stories that comprise American history. History is written by the “winners” and many times it can take decades or centuries for a more accurate picture to emerge from a situation.

For well over a century Native Americans were mostly portrayed as barbaric savages, and Euro-Americans as persons of upstanding character fulfilling God’s destiny. Then a new trend began of depicting the Native Americans more as innocents, and pioneers and settlers as egocentric, blood thirsty, greedy, and exploitative.

What is true? Most likely a balance of the two interpretations would be most accurate. That is what is necessary in the telling of the stories of our pioneer heroes of Tennessee – balance.

Description of Valentine Sevier

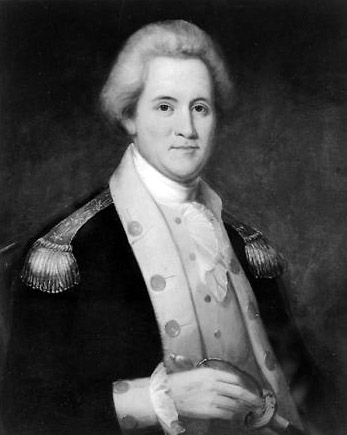

Our local Revolutionary War hero and settler was Valentine Sevier. He was adventurous, full of ambition, and willing to go to great lengths to achieve his goals.

He is the man whose name is emblazoned upon the plaque here in Clarksville at the site of Sevier Station; the man who is buried at Riverview Cemetery and whose life’s story and the sad ending filled with horrific violence is told and retold in Montgomery County; a life that began as the son of an immigrant living in Virginia in the 1740’s right on the edge of the frontier. And he is also the younger brother of the daring and ambitious John Sevier, who became the first governor of Tennessee.

His father was a Virginian of French extraction, from whom he inherited something of the Cavalier spirit so prominent in the character of his brother, Gen. John Sevier…with an erect, commanding, soldierly presence, bright blue eyes and quick ears…was remarkably fond of his horse, his wife, his gun, his children and his hounds…he was at once ardent, brave, generous, and affectionate…a man of strong intellect, daring courage, and inconquerable perseverance and great activity in the prosecution of all his undertakings…and he had a very large nose.”

What a wonderful description. And while it is evident Valentine had many admirable qualities, it should be noted that many men of his time were later described with the same romanticized language. Who were they truly?

Attitudes of the Overmountain Men

Yet, who they were and what they were doing is understandable if one considers the whole picture. To consider the life of Valentine Sevier one must put things in context. His life began as a little boy growing up in colonial Virginia (born 1747); a young boy who must have been frightened often by the continuous conflict with the Cherokee.

It is known that his father, Valentine “the immigrant” Sevier, had to move his family more than once in an attempt to ensure their safety. It seems many frontier families were reduced to feeling like nervous prey.

It is doubtful though that young Valentine understood the context and the overall picture that created this awful situation. Did he consider the Cherokee’s point of view as their lands were continually encroached upon and useless treaties continually broken? Did he understand the frustration and then later rage the situation produced for this group of people as well as other native groups?

And it should be noted, that is was not just Valentine, but the whole frontier system in the late 18th Century that was creating a violent and fearful situation. Valentine and his family were among many who were originally from Virginia or North Carolina and were pushing west in search of land and fortune.

Many in this group of Euro-American settlers had spent the 1770’s and the 1780’s in the Watauga Settlement, also known as the Washington District. This area is now in eastern Tennessee in the vicinity of Elizabethton and Jonesborough, which is Tennessee’s oldest town (est. 1789).

These settlers disregarded the treaties made between the British and the Cherokee in order to settle upon the land that they wanted. In fact, one could speculate the Revolutionary War for them was more about getting that land from the Cherokee than it was personal liberties. They were known for their brazen and independent leanings and also their abilities in the wilderness and with a musket – “The Overmountain Men.”

In 1774, Lord Dunmore of Virginia complained about them saying, “In the back part of this colony, bordering the Cherokee Country, there are a set of people who, finding they could not obtain titles to the land they fancied, have settled upon it and contented themselves to becoming tributary to the Indians, and have appointed magistrates and formed laws…Forming governments independent of his majesty’s authority, sets a dangerous example to the people of America.”

Independent. Courageous. Resourceful. These are all admirable qualities for sure.

At this point in his life (1770’s) Valentine was in his 20’s, had married Naomi Douglas, and started a family. By 1775 Naomi had given birth to four children and was also expecting twins. Valentine and Naomi Sevier would eventually go on to have 14 children together. It appears he originally supported his family by becoming a long hunter.

Later, after the Seviers had become part of the illegal Watauga Settlement he became a sheriff and justice of the court as well. As Valentine and Naomi were raising their young family on the western slopes of the Appalachians he and his brother, John Sevier, had gained prominence in their new community. He was also a Captain of the local militia and a spy which would lead him to become involved in many battles along the frontier with both the British and the Native Americans.

Years later Valentine’s nephew, James Sevier, reported the following about his uncle: “Although always in the militia (instead of the Continental Line or regular army), he was one of those spirits that never was missing at the post of danger until the close of the Revolutionary War.…There was no campaign from Lewis in 1774 until the close of the war in ’82 that he was not in against the Indians.…” He was part of the Battle of Point Pleasant against the Cherokee (1774), the Battle of King’s Mountain (1780), and then he and his brother, John Sevier, participated in the Overhill Cherokee expeditions (1779-1782).

These significant events in both Valentine and John’s lives took place while they were still relatively young men in their late 20’s and early 30’s.

The Seviers and the Cherokee

During the Revolutionary War the Cherokee aligned with the British against the colonists. This fact was beneficial in some ways for the opportunistic colonists who had illegally settled upon Cherokee land. The Overhill Cherokee Expeditions were dual-purpose ventures.

One purpose of these expeditions are reflected in the words of Valentine’s brother, John Sevier, relayed to us by Anthony Forman in 1789: “I heard John Sevier, at a public gathering of people on French Broad, stand up and inform the people .…you all will know that the Cherokees have refused selling their lands to us from time to time, and we have no other way now but to take it by the sword, by going into their nation, killing and taking their women and children, destroying their provisions, and by these means we will compel them to give up their lands to us.….”

The Cherokee had become perceived as a plague and a threat upon the settlements. In 1777, North Carolina enacted a new law. They had enacted this same law with similar verbiage a few years prior to rid the frontier settlements of “vermin”. The law had then been rewritten to deal with the problem that was the existence of the Cherokee.

The law was called, “An Act for the Encouragement of the Militia and Volunteers employed in prosecuting the present Indian War.” (Chapter VII, North Carolina. General Assembly April 07, 1777 – May 09, 1777). Any solider in the militia would be paid 10 pounds per Cherokee scalp and 15 pounds per Cherokee prisoner. But only after June first, it states. In effect, an open season of hunting had been declared upon Cherokees. If a person was not presently in the militia the payment was increased, “And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That a premium or reward of forty pounds for each scalp of an Indian Man, and a premium, or reward of Fifty Pounds, for producing an Indian Man Prisoner, be paid to any person in this State, not in the pay thereof who shall voluntarily undertake to make war upon the said Indians after the time aforesaid; …the Captors making oath as aforesaid, that such scalp or prisoner was taken by him after the said first day of June, and that the Indian so killed or taken was of the Nation of Indians commonly known by the name of the Cherokees; and that the scalp produced was actually taken from an Indian killed by the person claiming the same.”

As shocking as this law may sound, the people in North Carolina were not alone in the use of this method. It seems all groups during this period: the Spanish, the French, the Native Americans, the British, the Colonists, etc. could be found to be participating in scalping and paying for scalps at some point.

After the success of the Overhill Cherokee Expeditions, Valentine went on to become involved in the failed State of Franklin (1784-1788) along with the failed attempt to settle the Big Bend area along the lower Tennessee River near Muscle Shoals (1785 -1786). His next ambitious endeavor (and last) then became the creation of Sevier Station near the newly emerging town of Clarksville.

These goals and attitudes continued not just for Valentine, but his peers in the late 18th century. Many men who were part of the Watauga settlement, the North Carolina militia, or the failed State of Franklin had now embarked upon a new venture – the settling of and profiting from the Cumberland region. They realized there were fresh opportunities for wealth creation awaiting them.

Reading the correspondence between the prominent men of the time, it becomes clear that people were profiting greatly from buying and selling land grants originally awarded to Revolutionary War soldiers. Many men such as Governor Blount, James Robertson, and John Sevier were amassing tens of thousands of acres. They then appointed friends to the land registrar offices and surveyor positions. The Cherokee, the Creeks, the Chickasaw were an obstacle to their goals.

This type of pioneer was described in the book, Men of the Waters: “Among these pioneer land-seekers there was an occasional individual who had previously achieved a degree of material success on the former frontier… He was driven not by the necessity of seeking new opportunity but by an ambition to enlarge the scope of his enterprises.”

Valentine Sevier fits this profile. “When he crossed into the new country, he was able to carry with him several horse-loads of equipment, a small herd of livestock and a number of slaves to expedite the labor of developing his new property….Such more prosperous figures in the western movement were outnumbered a thousand to one by their poorer neighbors.…they usually became militia commanders, county lieutenants, convention delegates and the natural economic and political leaders of the new communities.”

So, the stage was set for what happened next. Valentine moved to the area of Clarksville, TN atop the bluff overlooking the Cumberland and the Red River. This was a prime spot for trade and future development with its two operating ferries, blacksmith shop, and the Sevier family name and prestige.

Unfortunately, like most of the other early settlers of middle Tennessee, he had settled upon the ancient hunting grounds of the Native Americans. Due to this fact, what followed next was an onslaught of raids and murder perpetrated upon the settlers along the Cumberland. Two of such incidents resulted in the horrific deaths of 6 of Valentine’s children and two of his grandchildren.

For over 200 years Valentine has been considered a hero and also a victim of tragedy. Yet, one wonders if this is a completely accurate interpretation. Is he a victim or is he also partly responsible for creating the tragedies which befell him?

If he could speak to us now, what would Valentine tell us about his life, the means he employed, and whether he regretted them? He could have made different choices and not lost 6 of his children and 2 of his grandchildren to an early grave. Not only that, but he lost his wealth as well due to the pillaging and burning of his station. At his death, records show he had a mere $6.32.

The stories of Valentine’s life and his contemporaries are something we can glean from. Through their stories and others throughout history we can contemplate the conditions that create conflict and tragedies. What are those conditions? And then this leads us to the question, what conditions cultivate peace?

In the end, maybe our ancestors from the 18th century gave us more than freedom from European powers. Maybe even when they failed humanity, they have given us lessons. May we not waste them.

Coming Soon:

Part 4: Is Sevier Station Really Sevier Station?

The artwork by David Wright used by permission. To see more of Wrights work, visit his website at www.www.davidwrightart.com

For more on the series, see: Clarksville Beginnings – Part 2: Revisiting the Massacre at Sevier Station; In Their Own Words