Clarksville, TN – Every human being has worth and deserves dignity. “Everyone matters” is an incredibly powerful humanitarian ideal, and one upon which the United States seems to continually both build and define. We hear the whispers of this ideal within the words of the Declaration of Independence.

Clarksville, TN – Every human being has worth and deserves dignity. “Everyone matters” is an incredibly powerful humanitarian ideal, and one upon which the United States seems to continually both build and define. We hear the whispers of this ideal within the words of the Declaration of Independence.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

The generation of Americans which fought to free us from the tyranny of Europe in the late 18th Century probably could not have grasped how these words, and the spirit of the ideal they reflect would be used by subsequent generations to form the nation we live within today.

Such was the case 150 years ago. Our present year, 2015, marks not only the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, but also the anniversary of the beginning of acknowledging the worth and dignity of all races of Americans.

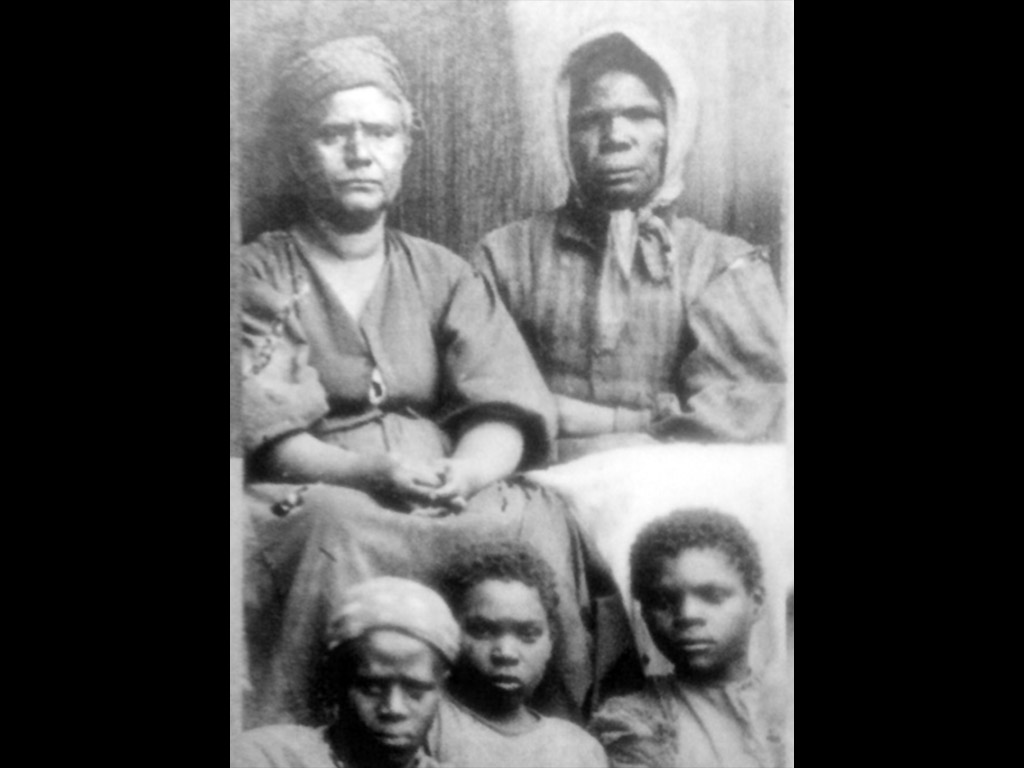

Like countless regions across the South, bridging that gap in Middle Tennessee was daunting. What happened to the men, women, and children who had been enslaved in Montgomery County? What did they do with their newfound freedom? What challenges did they face as they attempted to build a new life?

For the first time, the formerly enslaved men and women of Middle Tennessee would be able to assert their rights to not only receive pay for their work, but live where they chose, decide whom to marry, keep their children, receive an education, and to freely gather in their own house of worship. They carried within them the hope that they might possibly be able to experience free lives as equals.

Yet, even after the surrender of the Confederacy, many obstacles remained to this hope. One obstacle was racial beliefs. Prior to the war, the leaders of the Confederacy had made their beliefs and intentions clear concerning those enslaved in the South.

According to the Vice President of the Confederate States of America, Alexander Hamilton Stephens, their new government was founded “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

The declarations of the seceding states also proclaimed this attitude. The state of Texas, for example, declared their opposition to “the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color” and held as “undeniable truths that the government of the various States, and of the Confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity;” and that the African race, “…were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race”.

Consequently, even though the physical war was ultimately won by the Union 150 years ago and physical freedom attained in some form for many, these are the beliefs that freed men and women in Montgomery County and throughout the south continued to face.

First Tastes of Freedom

Before the defeat of the Confederate forces at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862 and the subsequent surrender of Clarksville, slaves had little chance of escape or emancipation from their situation in Montgomery County. Yet, after the Union troops arrived to occupy Clarksville, opportunity began to show itself.

Enslaved persons began to leave their masters and seek refuge among the Union troops, especially around and near the earthen fort, Fort Sevier, presently called Fort Defiance. The fort had been built on the bluff above the confluence of the Red River and the Cumberland River only a few months before this time by the forced labor of approximately 200 slaves. After the fort’s surrender, the occupying Union troops would quarter and protect them, yet in the beginning some soldiers would return them to their masters.

There were approximately 3.9 million slaves in the United States in 1861 with over 275,000 residing within the state of Tennessee. Nationally, approximately 500,000 were able to escape their masters. White citizens in the area were greatly displeased with the upheaval and change occurring. Even persons who chose to stay with their previous masters began negotiations for better accommodations or even compensation for their work. The status quo was finally beginning to shift.

Freedmen camps for refugees began to emerge in 1862 and, in Clarksville, the first camp consisted of 2 large buildings which housed approximately 200 people. Many persons in the camp were illiterate and now also lacked employment, adequate housing, and sustenance. Yet, for the first time in their lives the camp inhabitants were allowed to legally receive education. Northern missionary aid societies provided teachers to give instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, as well as industrial training in the south.

The Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission provided 6 teachers to the Clarksville camp itself. Also during this time, General Grant appointed John Eaton as the “Superintendent of Negro Affairs in Tennessee” with the responsibility to protect recently freed slaves. Mr. Eaton then appointed superintendents at the various Freedmen Camps. By 1864 the camp in Clarksville had numbers that swelled to over 3,000 refugees in a town that previously was home to only 5,000 citizens before the war.

The next progressive step towards equality occurred in January of 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This proclamation not only freed slaves in rebel states, it also granted black men the right to fight for the Union. The United States Colored Troops (USCT) was created, and many served valiantly in an effort to ensure their continued freedom. An estimated 1800 freedmen joined the 16th USCT and 9th US Colored Heavy Artillery in Clarksville during the Civil War. In September of 1865, the Chronicle reported that the city was garrisoned by the USCT and claimed this to be an “uncalled for outrage and insult”.

In 1865, the federal government officially established the Freedmen’s Bureau with the purpose of assisting men and women in their transition to life as free persons. The Bureau assisted with education, negotiating labor agreements and also basic needs like food and clothing. In August of 1865, the Chronicle explained the purpose of the Freedmen’s Bureau to the citizens of Clarksville, and by the following January it also proclaimed the first day of the new labor market where the Bureau assisted with the hire and contracting of laborers with planters.

A model for labor contracts was adopted by the Freedmen’s Bureau from local plantation owner, J.B. Killebrew. He had been proactive in searching for ways to rectify the new labor situations years prior to the end of the Civil War. In his opinion, “All the traditions and habits of both races had been suddenly overthrown and neither knew just what to do or how to accommodate themselves to the new situation. For this reason I drew up the rules and regulations referred to.” During this same momentous year of 1865, the 13th Amendment was passed officially abolishing slavery in the United States.

Education – Obstacles and Opposition

By April of 1866, the Freedmen’s Bureau reported that there had been a drastic reduction in the amount of black students and teachers in Montgomery County. There were 266 students attending in the county putting to use 4 schools and 4 teachers, while previously there had been over 1,500 students. In 1868, there was one school in New Providence near Trice Landing.

There were also 3 schools south of the Cumberland River: one at Round Pond, one at Cumberland Furnace, and one at Cabin Row. There were also schools in the basement of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church as well as the “Cincinnati” School run by the Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission. Unfortunately, during this time the aid from the missionary societies began to decrease. They were not well received in Clarksville and were commonly seen as a sign of continued federal control. The “Cincinnati” School closed in June of 1867.

The school at Cabin Row had been built by monies raised exclusively by the Freedmen themselves and had about 30 children attending. Yet, in March of 1868 riders came by night and attempted to burn down the school. Fortunately, Freedmen were able to put out the flames and save the building.

Throughout the county the newly emancipated citizens showed their support of education by finding funds to contribute to the pay of their teachers. The teacher at the New Providence freedmen school was a young teacher named Miss Maggie Horton. Her pay was $20.00 a month to teach 80 eager students with many on a waiting list. The Freedmen in New Providence had been able to raise well over half of the expense to build a new school. Yet, it was already full to capacity. Miss Horton sought to find an additional building in the community and met much resistance. She requested the rental of one building and the response of the owner was that he would rather “burn it to the ground than rent it” to the freedmen.

Violence against Freedmen schools and their teachers was pervasive during this period throughout the state. Several teachers were killed and some attacked and beaten. A total of 37 schools were burned. Violence was also occurring at the local furnaces and ironworks where many freedmen were now employed versus enslaved.

At its root, the violence stemmed from a fear that the freedmen would reach equal social status with white citizens. Eventually, a level of acceptance, albeit low, settled over the area as a statewide school system was put into place for the first time in Tennessee in 1868. Even though the Freedmen had gained the freedom to learn to read and write for the first time, the era of segregated education then began. Still the result was tremendous for its time. Many adult Freedmen were able to learn to read and the future possibilities for the lives of the young students were greatly expanded.

Consequently, as former slaves continually gained rights, fear spread amongst white citizens of the possibility of experiencing social inequality and oppression themselves. This fear gave birth to violence and the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan regularly met at both Dunbar Cave and the basement of Stewart College and undertook violent activities with the intent of intimidation. Racial tensions grew as white citizens sought to maintain racial dominance.

Financial Disparity

After the war, the Freedmen started to move away from the camps and explore their options for employment and housing. This proved very challenging at times, and residents especially out in the county, began to complain of theft as desperate men and women sought to avail themselves of necessities. The intent of the Freedmen’s Bureau was to assist with such transitions into life as freed persons.

Looking at the data it is evident their success was limited and, despite assistance the promise of freedom turned out to be a bleak reality for most. The promise of “40 acres and a mule” seemed to quickly fade into a fantasy idea. Despite original plans to the contrary, Confederate veterans would indeed hold onto their land rights, and the newly freed men and women would begin their new lives with little or nothing. Yes, the enslaved had become free, but they were given little or no share of what remained of the assets of the South after the war – mainly land and property.

They were left to forge a future with only their labor and nothing else. Add to this dilemma the fact that the vast majority of Freedmen were illiterate since they had not been allowed to receive education, or even training in some type of trade. Before the war, many of the enslaved in the area worked for tobacco planters or as household servants. Also, it was common for the local iron furnaces to use slave labor.

Data compiled specifically from the 1870 census in Montgomery County by local historian, Dr. Richard Gildrie, gives one a sense of the realities many former slaves experienced in the area in relation to their occupations and property ownership. This particular data pertains to the families and properties “near old fort” and “near Atkinson house” which is presently the neighborhood near Fort Defiance Civil War Park in the New Providence area of Clarksville, Tennessee (known in the 1870 census as District 7).

The data reveals that former slaves were a slight majority population within this particular neighborhood. The total population of District 7 was 1,119. It listed 601 persons as black and 518 as white.

The census also reveals that the majority of black residents were not born in Tennessee which suggests they were relocated, most likely due to slave trading or due to becoming refugees during the Civil War. It is also apparent that multiple families living within one home were more common than in white households. The literacy rate among adult Freedmen remained low, yet their children were receiving education in record numbers.

Also, the economic disparity was vast and it is evident that efforts to integrate former slaves into free society were an economic failure. It seems the adults hoped for a different outcome for their children as they supported their local schools and consistently sent their children to attend. Until then, the following table illustrates the extreme difference in assets according to race despite the fact that Freedmen consisted of the majority of the population in the neighborhood.

Table 2: Personal Property and Real Estate Comparison of District 7 in 1870

Black Households $2,900 (Total Real Estate Value) $2,250 (Total Personal Property)

White Households $137,775 ( Total Real Estate Value) $121,900 (Total Personal Property)

Disadvantage is also reflected according to occupation. Occupations at the time were general labors or farm/agriculture work, but also artisan occupations such as tailors, coopers, or blacksmiths. There were also retail jobs such as grocers, dry good merchants, and store clerks.

The table below reflects the extreme disparity of employment opportunity in 1870, and it should be noted that at this time only white males held professional jobs in District 7 such as physician, banker, or college professor as well as government positions such as Justice of the Peace or Constable.

Table 3: Occupations of Adult Males of District 7 in 1870 Census

Black Males Laborers (84) Artisans (5) Retail (2) Government (0) Professional (0)

White Males Laborers (9) Artisans (29) Retail (30) Government (5) Professional (12)

Maybe what continued to be the biggest disparity still were racial attitudes. The local paper published articles disparaging the Freedmen proclaiming their homes to be dirty and grotesque and also printing articles that supported the belief that those of African descent were inferior and destined to servitude.

An educator and activist of the time period, Harriet A. Jacobs, spent substantial time within the contraband camps and new Freedmen’s schools. She entreated others to put aside their prejudices and to give the former slaves opportunity.

“Trust them, make them free, and give them the responsibility of caring for themselves, and they will soon learn to help each other. Some of them have been so degraded by slavery that they do not know the usages of civilized life: they know little else than the handle of the hoe, the plough, the cotton pad, and the overseer’s lash. Have patience with them. You have helped to make them what they are; teach them civilization. You owe it to them.”

Religious Freedom

One can imagine with so much around them feeling dark and oppressive, that the Freedmen sought ways to bring hope and light into their lives. Spirituality was one avenue of doing so. Near the Freedmen’s camp around Fort Defiance, former slaves began openly having religious meetings, something that had been previously forbidden.

In the past, white citizens feared such meetings would be used to encourage insurrection. Before the newly formed congregation could raise a building, they met under a simple open-sided wooden structure with a roof made of brush from the surrounding woods, otherwise known as a brush arbor. A building was raised for this congregation in 1865 and the church officially established.

Greenhill Church continues in ministry today and is presently located on Walker Street just around the corner from Fort Defiance Civil War Park. The original building was built upon the bluff overlooking the Red River to the east, but was destroyed by fire in 1959. The present building was moved to Walker Street from Fort Campbell, Kentucky. It is a congregation begun by freed men and women “banning together to witness the fulfillment of prayers, hopes, and dreams.”

Lessons from History

150 years after the Civil War was fought and the Confederate States of America were defeated, the United States still struggles with racial tension. The effect of the war, the abolishment of the institution of slavery, and how both southern communities and the federal government handled the aftermath can still be felt today. The newly freed slaves initially experienced a tremendous expansion of liberties and opportunities.

Unfortunately, due to the political climate of the following decade and the fears of their fellow white citizens, they then experienced a great withdrawal and limiting of those same liberties. True, they were granted the right to vote and participate in government, yet by the end of the century Jim Crow laws were firmly in place ensuring great limitations of those rights and their status as second class citizens.

The forced labor of slaves was the very foundation of the southern economy before the war. Due to their sweat, toil, and suffering much of the tobacco, cotton, and other crops in Tennessee were harvested, bringing recompense to their masters. Due to the grueling labor of enslaved iron furnace workers and miners, even more prosperity was brought to the area. Why should they have not received something in recompense? Yet, it is questionable that this policy would have been feasible and whether it would have incited further violence. If this policy had been enacted then how might it have changed the subsequent events that created further racial tension in the South?

Despite the continued hardship in the struggle to be free and equal, many former slaves continued in hope. By the end of Reconstruction (1877), life in the South had returned to a social and economic order that was strikingly similar to what had existed before the war. Yet, the ideal that fueled both the Civil War and the Revolutionary War remained beneath the surface, not yet fully taking shape as a reality – the ideal that all are created equal and that all human beings are deserving of dignity and respect. Ideals are powerful intangibles and though they seem defeated at one point in history they may become reality in subsequent generations. History reveals this truth.

Many ideals might seem fanciful and unrealistic, and the effort to create change insurmountable, but once again history gives us lessons. And so, as the former slaves found strength to dream and hope for progress, may we be encouraged to do the same, no matter the issue.

Love the new piece Tracy!