Clarksville, TN – Have you heard the story of the first frontier settlement on the Red River?

Clarksville, TN – Have you heard the story of the first frontier settlement on the Red River?

Many times the history beneath our feet here in Montgomery County is not in the forefront of our minds. It can be easily forgotten that the many places we live, shop, or work every day contain stories from multiple historical periods of Tennessee. In this case, it is the history of westward expansion and the Indian Wars of the 18th century.

People may wonder why these stories matter. Many of us were at one time young students who felt history class was incredibly boring and even called it our least favorite subject. Yet, in truth, it is those who devote some time to the subject in depth who are a very fortunate group of people. They gain insights and knowledge; they increase their wisdom.

History at its most interesting is when we are able to read the very words of someone from the past, stand where they stood, see what they saw, touch what they touched. It then becomes so very real. And fortunately, we can do many of those tangible things when it comes to the frontier period of Tennessee.

In particular, we have many first person accounts due to the existence of the Draper manuscripts. Testimonies of the men and women who lived through the frontier period of Tennessee were carefully collected and preserved by 19th century historian, Lyman Draper, before all of the persons involved passed away, thus taking their experiences with them.

Some of these first-hand accounts shed light upon the story of the ill-fated Renfroe Station, which was a frontier station that existed right here in Montgomery County, upon the Red River at the mouth of Passenger Creek. It was one of the first attempts by Euro-Americans to live in this area.

The story of Renfroe Station is interesting and meaningful, but also horrific. The deeper reasons as to what happened to this group of settlers are still relevant to our lives today. Some of the elements within the story continually repeat themselves amongst people and having been doing so for thousands of years.

It demonstrates the pattern of violence which can occur when one group disrespects or disregards another. It also demonstrates the innate need for human beings to seek adventure, to build, to create, and to take risks; all the while noticing that others are more drawn to sameness, the status quo, and the ever elusive feeling of security in a world full of unpredictability. It all creates a rather fascinating story.

Travelling to Renfroe Station – Richard Henderson and the Transylvania Land Company

It is a story which actually begins with a man named Richard Henderson, the enterprising owner of the “Transylvania Land Company”. Shortly before the Revolutionary War, Henderson made an agreement with some of the Cherokee in which he thought he and his investors had purchased all the land north of the Cumberland River, southeast of the Ohio River, and west of the Cumberland Mountains. The purchase of approximately 20 million acres became official in 1775 and was known as the “Sycamore Shoals Treaty”.

Henderson was a land speculator and intended to greatly profit from the purchase and must have been elated with his somewhat risky, but likely lucrative investment. But, there were problems with the presumptuous purchase, and as history shows us, sometimes things do not go as planned. There were multiple groups that were uncooperative and not willing to go along with Henderson’s enterprise.

When the British had controlled the colonies it was known that the lands west of the Appalachians were to belong to the Native Americans, all according to treaty between the indigenous people and the British crown. Yet, there were some, of which Richard Henderson was a party, who felt they could supersede this authority. Of course, superseding British authority was an increasingly popular idea during this time.

The year following the treaty, the Virginia legislature refused to recognize the purchase and nullified Henderson’s agreement, and later North Carolina would do the same. They did, however, award him 200,000 acres in what is now middle Tennessee as a consolation of sorts.

The question then remained as to how Henderson would motivate settlers to embark on the proposed expedition. How did he convince people to expose themselves to such danger? He promised the pioneers the allure of land and opportunity, but likely failed to emphasize the mortal danger that would be involved.

That leads us to the most significant obstacle to Henderson’s plan, the existence of a group of Native Americans who vehemently opposed the treaty at Sycamore Shoals. It is true that several Cherokee leaders were in agreement with the treaty, but not all. One chief in particular, named Dragging Canoe, did not sign the treaty.

In 1777 he then led a group of Cherokee that were particularly hostile to settlers down the Tennessee River to settle near Chickamauga Creek, thus gaining the name of Chickamaugans. Unfortunately, that was exactly the river the pioneers were to travel upon to reach their final destination. Would you have gone?

A group of 300 settlers did decide to go and they went for varying reasons. Some were already wealthy, had prestigious positions, and were looking to expand their enterprises. Others were vulnerable due to their need for opportunity. Yet, either way, this group of colonists, recently turned Americans, were readying for a journey upon the river systems of present day Tennessee. They looked west with dreams of expansion, wealth, and adventure. It was a journey that would bring them to present day Montgomery County.

The Donelson Flotilla

By the fall of 1779, Richardson and Donelson had found a group of settlers who were ready to embark on the risky journey. One young pioneer named Johnson Farris later explained that “…in 1779 Colonel John Donelson informed the citizens of Halifax County, Virginia, that the government had offered a bounty of land near the French Lick on Cumberland River to any male 21 years of age and upwards who would become a citizen, build a cabin, raise corn, and be willing to encounter danger and privations.

I was 18 years of age, impelled by a desire to better my condition in life, and I determined to accompany Colonel Donelson, not doubting that if I served I should receive the promised bounty.” Farris along with over 300 more souls agreed to attempt to settle the area by establishing frontier stations from which land surveying and speculation might proceed.

Elijah Farris also recalled, “Colonel Donelson offered 640 acres to every man who would go and raise a corn crop on the Cumberland. I am listed (sic), and got to a little below the big island late in the fall of 1779.” Elijah was referring to the Long Island of Holston River in present day eastern Tennessee.

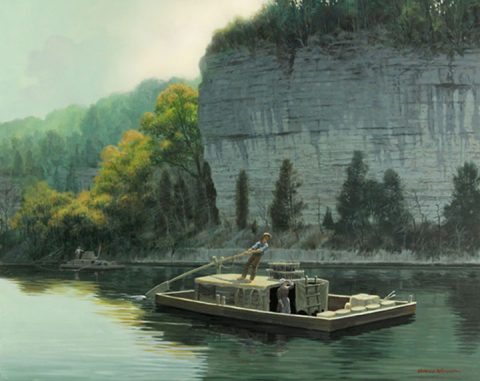

It was there that the group of settlers assembled, camped along the river, and built 40 flatboats for the journey. They were then to travel from Fort Patrick Henry, down the Holston River, down the Tennessee, to the Ohio, and then over to the Cumberland on their way to French Lick and Heaton’s Station, or present day Nashville.

The Donelson flotilla was not the first to undertake this journey. Others had in fact gone before them, as colonists explored the possibility of using the rivers as trade routes and then also explored the nearby land for suitable settlement locations. Due to this fact, the group was prepared with knowledge of particular landmarks and approximated distances.

Not only had British colonists become interested in navigating the rivers, but preceding them, the French coureur des bois (“runners of the woods” or fur traders) had developed trading posts and relationships with the Native Americans living in the area.

In December of 1779, they officially began the journey. John Donelson described their endeavor in his journal as “intended by God’s permission in the good boat Adventure, from Fort Patrick Henry, on Holston River, to the French Salt Springs on Cumberland River.” The group consisted of men and women, adults and children, both free and slave.

Detailed information survives about several of the pioneers and their boats. Robert Cartwright built his boat with a “…small brass cannon…mounted on the boat, and there were rifles and muskets for all who could fire a gun. His boat had room for three families, besides a number of negroes. Two of the negroes…were girls, Aliph and Susan, aged 15 and 13 years old.” (L.C. Bell, 1936) Also, before leaving his previous home in Watauga, Cartwright “…provided himself with cuttings of apples, and perhaps other fruit, packed in kegs of clay, for the purpose of raising an orchard.” (Andrew Cotton Cartwright)

Part of Colonel Donelson’s personal boat was roofed, and about 15 whites and 30 slaves were in his group, a fraction of the overall total of 300 persons. “When camped on shore of nights, the campfires, strung along the bank, made quite a show”. (Mary Donelson) Donelson’s boat was also used for a school for the children. Approximately 20 or 30 children were taught during the week by James Robertson’s sister, Mrs. Ann Johnston. She also conducted a Sunday school on the Sabbath for the children. (C.D. Elliot)

There is no record of trouble during the first couple months of travel. Yet, by March of 1780 the group had progressed down the Tennessee River and reached the domain of the Chickamauga. At first they met a couple of Native Americans who showed signs of friendship, but the situation quickly changed when they came upon one of the Chickamaugan towns near the shore of the river.

This group was particularly opposed to any new settlements or treaties, and a nightmarish scene soon unfolded. This new endeavor to survey, settle, and sell the land of the area was not consensual amongst all who lived there. The people who called the area their ancestral hunting grounds were being invaded and they knew it. What happens when one group disrespects and dispossesses another? Usually resistance and then many times violence.

Strangely enough in this particular situation, the violence began in the most innocuous manner. Mary Donelson, one member of the group, later shared, “…some heedless young fellow on one of the front boats shot a swan in the river which, some surmised, roused the Indians, thinking perhaps it was intended to intimidate or defy them. The Indians immediately commenced firing.” The pioneers immediately returned fire from their boats and one young man, John Payne, was shot through.

“On board the boat of Mr. Stewart were blacks and whites to the number of twenty-eight souls. His family being diseased with the smallpox, it was agreed that he should keep in the rear for fear of spreading the infection…the foremost boats having passed the town, the Indians collected in considerable numbers. Seeing him far behind the boats in front, they intercepted him in their canoes, and the crews of the other boats were not able to relieve him. The whole crew was killed or made prisoners. The crews perceived large bodies of Indians marching down the river, keeping pace with the boats till the mountain covered them from view. The boats hoped the pursuit was over. The boats then arrived at the Whirl, or Suck, where the river is compressed into less than half its usual width. Passing through the upper part of these narrows at a place …termed the Boiling Pot.” (John Donelson, Jr. & Mary Donelson)

After the loss of the Stewart family all 40 boats had to pass through “the Suck” in order to continue and most importantly leave the domain of the Chickamauga. The Indians knew this and “… ran across the bend, perhaps four or five miles to the Suck, and fired on the boats again,” reported Elijah Farris.

He went on to say, “At first the boats attempted to go on one side or the other, but failing, all passed through the center – some boats running against each other…the collision threw me into the water. I seized a rope attached to one of the boats, and was pulled in. By a great deal of rowing, the boats all got through the suck – a canoe of goods got loose from one of the boats and was left whirling in the stream, with a dog in the canoe.”

Also during the attack, the Gower family’s boat was in distress as Indians shot down upon it and four persons were wounded. John and Mary Donelson later relayed that “…the crew was thrown into disorder and dismay, and his daughter, Nancy Gower took the helm and steered the boat, exposed to all the fire of the enemy. A ball passed through her clothes and penetrated her upper thigh, going out the opposite side.”

Nancy did not even realize she had been shot until the fighting was over. Her mother noticed the blood on her dress. She was very fortunate and later made a complete recovery. Others were not so lucky.

During this same attack young John Jennings and another man decided to swim ashore and give themselves up. The other man was immediately tomahawked and Jennings taken captive. During this mayhem his father, known as old Mr. Jennings, was in a panic and intended to lighten his boat in order to free it from where it had become stuck on a rock. His family began to help him by throwing as many items as possible out of the boat, desperately wanting to leave that nightmarish segment of the river.

It just so happened that the night before, old Mr. Jennings’ daughter had given birth to a child. In the confusion they threw the blankets and bedding into the river and tragically also amongst the blankets was the infant. The deep sorrow of that moment is hard to fathom. They only discovered later, once it was too late, what had happened.

I wonder if this group had known their fate, would they still have gone? It is true that when we are within a situation it is harder to see it for what it is and to have perspective. From our standpoint, the violent outcome of Richard Henderson’s Transylvania Land Company seems highly likely.

The members of Donelson’s flotilla either did not fully understand this or the chance of success was just too attractive. Like us, they lived in a world full of both possibilities and unpredictability. Yet, it could also be argued that it is that unpredictably that keeps life interesting and makes it an adventure. When nothing is certain, anything is possible.