Clarksville, TN – In the South, old-timers tell children, “Long ago, squirrels could run in trees from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River without touching the ground.” Austin Peay State University (APSU) professor of Biology Dr. Dwayne Estes hears that often and knows it’s not always polite to fight over Southern folklore.

Clarksville, TN – In the South, old-timers tell children, “Long ago, squirrels could run in trees from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River without touching the ground.” Austin Peay State University (APSU) professor of Biology Dr. Dwayne Estes hears that often and knows it’s not always polite to fight over Southern folklore.

“Sometimes you just have to pick your battles,” said Estes. “It’s hard for people to realize that prior to the 1930s, fires maintained large expanses of pine-oak savanna, woodlands and glades in the South’s Interior Grasslands region, which includes the Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia and Alabama,” Estes said.

As executive director of the Southeastern Grasslands Initiative (SGI), located at APSU in Clarksville, Tennessee, Estes leads SGI’s team of researchers, conservationists and industry partners who are working to study, restore and rebuild the South’s long-forgotten grasslands.

“For thousands of years before the arrival of Euro-American settlers, widespread natural processes such as fire and grazing and browsing by bison and elk herds helped maintain the open condition of Southern prairies and savannas,” Estes said.

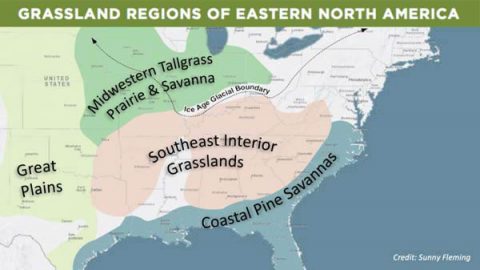

“Many people are familiar with the Great Plains, but most don’t know that major portions of most Southern states were covered in grasslands as well. They could not rival the Great Plains in sheer size, but what they lacked in expanse, they made up for in diversity — both of grassland types and species. Those squirrels, in reality, wouldn’t have gotten very far.”

What Changed?

By the early 1800s, the bison and elk were a distant memory, but wildfires still burned across parts of the Southern U.S. into the early 20th century, though less frequently. By the 1930s, the last of the once-open savannas of the Cumberland Plateau began to close in with dense trees for the first time in a few thousand years.

Throughout the 20th century, the South’s naturally open landscapes continued to suffer — fires were suppressed, forests thickened and the rich wildflower patches and shrub thickets of the former grasslands died out.

“The thick forests the public views as being the natural condition now are in many places unnatural artifacts of fire suppression; they used to be our Southern grassland ecosystems,” Estes said.

“Many southern grassland ecosystems are nearly extinct, and the plants and animals that depend on them are fading fast,” said Theo Witsell, SGI’s co-founder and chief ecologist. “Between past conversion of native prairies to row crop agriculture and the intensive grazing and planting of non-native pasture grasses in our savannas, only scraps remain in many areas to sustain native grassland species. Add in habitat fragmentation and fire suppression, and we are seeing a landscape-level conservation crisis.”

Dr. JoVonn Hill, an assistant research professor with the Mississippi Entomological Museum at Mississippi State University who regularly collaborates with SGI, agrees. “Habitat loss is the primary cause of the decline of our native bees and butterflies, which are important pollinators, because many of these insects require specific species of native grassland plants to complete at least one part of their life cycle.”

Furthermore, data and studies from many different sources indicate that birds and certain small mammals, reptiles and amphibians that are grassland-dependent are in steep decline.

Estes explained that restoring native grasslands is necessary, because they are vitally important for water quality, soil health, carbon storage, drought protection, and wildlife and pollinator habitat.

Helping Hands

As luck would have it, the Great Depression and the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1933 came in the nick of time to save the region from poverty and also to help save some pieces of our ancient Southern grasslands.

TVA botanists have been roaming the Tennessee Valley since the 1970s, looking for areas that contain endangered plants and unique habitats such as grasslands. While TVA power lines were created to transmit electricity, by the early 2000s it was becoming clear how important transmission lines are for protecting biodiversity of species that require open, prairie-like habitats.

In 2018, TVA reached out to SGI and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) to help develop a research study that seeks to quantify the significance of these important habitats, focused on the Cumberland Plateau. The Mississippi Entomological Museum (MEM) was brought on board to help understand pollinator use of these areas.

According to Estes, TVA power lines represent some of the last vestiges of a hugely diminished grassland ecosystem, where shortleaf pine-post oak savannas once covered hundreds of thousands of acres of the Cumberland Plateau. The data gleaned from this project, which focuses on the Plateau in in Alabama and Tennessee, will provide vital information on how and where to protect and expand these important habitats.

“This study will build on our work to understand the role TVA power lines play in supporting pollinators and plants associated with grasslands,” TVA Botanist Adam Dattilo said. “We want to put the ecological value of these grasslands into context, and the data collected will help us tell that story.”

TVA’s Biological Time Capsules

Dattilo leads TVA’s efforts to study how the largest public power utility in America can support pollinator habitat along its 16,000 miles of power lines.

Many TVA power lines were built during the 1930s — just as the open savannas began to close. These power lines formed biological time capsules allowing species that once occupied millions of acres of savannas to continue to survive in narrow strips — some as little as 50 to 100 feet wide! “Many people,” said Estes, “are surprised to discover that these power line corridors are actually the closest thing to the original landscape of the Cumberland Plateau as it would have appeared in the 1700s!”

“Emerging research tells us that the power line corridors are critical to the conservation of pollinators, rare plants, and many other animals,” Dattilo said. “It’s extremely important to manage these corridors properly to promote positive environmental outcomes while at the same time ensuring the safety of the electric grid.”

“Most people know us as an energy company, but TVA is on the forefront for protecting the environment,” Dattilo said. “Partnering with SGI and EPRI is one step in TVA’s journey to preserve grassland habitat at strategic locations across our region.”

These remnant “time capsule” grasslands will likely become vital to the restoration and expansion of native grasslands across the Plateau, by providing locally adapted seed sources for a wide variety of both common and rare native plants.

Putting Seeds to Work

In January 2019, 50 volunteers braved cold weather to support SGI’s inaugural restoration event at Dunbar Cave State Park near Clarksville, Tennessee.

The team spent the day planting native seeds by hand and clearing invasive species. By the end of the day the volunteers had worked on about 15 acres. “The seed stock used for this and other grassland restorations originally comes from remnant native habitats such as those in the TVA power line corridors,” said Witsell. “That’s another reason why this project is so important. They are literally the seeds for the grasslands of the future.”

The time spent clearing and reseeding was well worth the effort. Estes surveyed the work this summer while Tickseed Sunflower and a variety of showy wildflowers and grasses were in bloom, and he was optimistic about the results.

“While the scientist in me knows it can take decades to restore habitat, I’m pleased with the Dunbar results,” Estes said. “With the help of our partners and the public we can make an important positive impact on the world around us.”