In honor of women’s history month let me share with you the story an intriguing woman in Clarksville’s history, Lulu Epperson.

Clarksville, TN – Amidst the mayhem of 2020 there was an important anniversary that not everyone may have noticed. August 18th, 2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment, which resulted in giving women in the United States the right to vote.

Clarksville, TN – Amidst the mayhem of 2020 there was an important anniversary that not everyone may have noticed. August 18th, 2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment, which resulted in giving women in the United States the right to vote.

At the same time that we marked that anniversary, we were once again facing the effects of racial oppression from our past that continues to reach into our present. What do these two topics have to do with Lulu Epperson? Quite a bit, actually.

There are a lot of old stories embedded in the dirt of Tennessee. All types of people have lived and died here, but they are not just ashes to ashes, dust to dust. They have left their marks and affected the conditions of the lives we live today.

They were inspiring and heroic people, confounding people, and sometimes very complicated people. Often the themes woven throughout their lives are straightforward, but sometimes, they are truly a dichotomy. Such was the case of Lulu Epperson. She was complicated, just as our country’s history is often complicated.

I first noticed Lulu’s name while on a tour of Dunbar Cave. One of the best parts of the cave tour is reading the names written on the walls and ceilings of the different cavernous rooms. There her name was, written with candle soot over 130 years ago, and so very well preserved in the cool air of the cave. Dunbar Cave is more than a natural wonder; it is also a well-preserved autograph book from Clarksville’s colorful past.

Not long after I noticed Lulu’s name in the cave, local historians began researching the women’s suffrage movement in Clarksville and Lulu Epperson’s name began to surface more and more. I decided to delve further into her life and discovered that she was a very interesting woman. She was heavily involved in two particular issues that continue to affect our lives today.

Lulu was born in Clarksville in 1870 and was the oldest of Billy and Sallie Bringhurst’s 10 children. The Bringhurst family was well known in Clarksville during their time. They ran a prominent hotel for decades, called “The Franklin House,” which used to be located where the F&M Bank now stands on Public Square. It was at the hotel that Lulu spent her childhood, watching visitors from all walks of life pass through its doors: dignitaries, performers, steamboat men, traveling salesmen, minsters, and, of course, leisure travelers.

How many dinners did she witness in that busy hotel dining room and what types of interesting conversations did she overhear? Her life and the life of her family orbited around the hotel and its visitors. Their schedules were often determined by the arrival of steamboats and also the railroad schedule, as people came and went accomplishing their business in Middle Tennessee.

It was there that Lulu must have begun to observe the different roles allowed to men and women in a bustling southern town. It was also there that she witnessed the jobs allowed, or not allowed, to those who had previously been enslaved. The cooks and maids at the hotel were Black women, as was “Mammy Susan,” the woman who helped care for the Bringhurst children. It must’ve been evident to Lulu from a young age, that her world had rules and that true opportunity, freedom, and choices were given to certain people, but denied to others.

Achieving Despite Limitations

By all accounts, Lulu grew up to be a remarkable woman. She was intelligent, articulate, and a gracious host. She was also a leader by nature, just like her grandfather who had at one time been the mayor of Clarksville. While the realms of business and politics were the domains of men during her time, it was acceptable for women to become part of community groups such as historical societies and garden clubs. Lulu was often found to be a leader in these organizations.

At first, in all respects of life, Lulu followed a traditional path. At the age of 18, she married William Epperson, they made a home together and began a family. Yet, soon she would become no stranger to heartache. Lulu and William’s 4-year old son died of diphtheria in 1897 and then, two other babies died in infancy. Their only child to survive into adulthood would be their daughter, Sarah. Then in 1900 tragedy struck again, when Lulu’s husband died of pneumonia. At the age of 30, she had become a widow and on top of grieving a succession of deaths, she was left with no means of support.

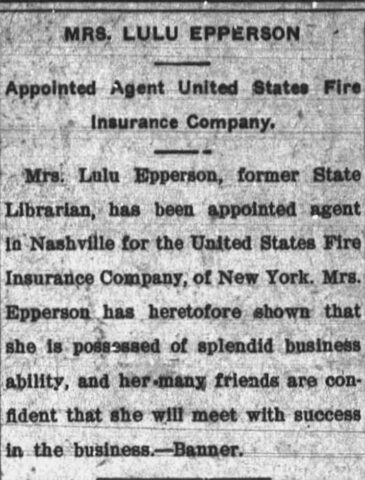

Being a woman in a man’s world became a stark reality for her, but her grit and determination became obvious. In 1901, she landed the position of Tennessee State Librarian in Nashville. One local paper wrote about her, “Mrs. Epperson could not fail of courage when left in life dependent upon her own exertions. Feeling that she was competent to fill the position, with a laudable ambition, she sought the highest honor the Democratic Party and the people of Tennessee could bestow upon a woman….with her natural talent to direct, a personal magnetism almost unsurpassed and by dint of a determined will, she at once stepped to the front of the candidates….”

Her activities and accomplishments over the next 20 years were remarkable when considering the time period within which she lived. After the state librarian position ended, she started her own insurance company in Nashville. During this time, a group of businessmen sought to run her out of business, but instead of retreating and accepting defeat she sued them for their actions and won!

She decided to return to Clarksville in 1914 and sought public office once again and ran for the position of postmistress. Unfortunately, she was disqualified from the race simply for being a woman. In 1918, she became the manager of the Montgomery Hotel in Clarksville (which at one time had been called the Arlington Hotel). The hotel was located on 2nd Street across from the county courthouse, where a marker still remains. The Montgomery Hotel was an improvement compared to her parents’ hotel. Its amenities included hot and cold running water, steam heat, its own barbershop, telegram office, and billiards room. The walls were three feet thick which made the rooms quieter despite the bustle of the hotel.

Yet, the most historic aspect of the hotel is that Lulu used it to provide space for something the world had never seen before, a bank owned by a woman and also completely run by women. It was called “The First Woman’s Bank of Tennessee” and Lulu became the bank’s first depositor. It was uncommon to give women possession of and access to their own money, but Lulu and others had realized its importance.

She also started Clarksville’s first Democratic Women’s Club and held the meetings in her hotel. By this time, the barriers to women’s political involvement had become abundantly clear to her, and Lulu became an enthusiastic supporter of women’s suffrage and the chair of Clarksville’s League of Women Voters.

She had realized through her own experiences that women needed a voice, more rights politically and financially, more opportunities, and more equality. Sometimes experience is the best teacher.

Lulu Epperson and the United Daughters of the Confederacy

Gender was not the only thing that made a significant impact on Lulu’s life. In the same year that she fought to give women the right to vote, she also became the Vice President of “The United Daughters of the Confederacy” for the state of Tennessee. Lulu was a staunch supporter of the Confederacy, its cause, and its memory.

She held the meetings of Clarksville’s UDC chapter at her hotel and for decades she is mentioned within all the local announcements of their ceremonies and meetings. This was not a passing or thoughtless association on her part.

Why was she so drawn to this group and from where did her passionate loyalty come? One of the most significant and central relationships throughout Lulu’s life was her relationship with her father, Billy Bringhurst. He was both her father and her business partner. William “Billy” Bringhurst was well-known in Clarksville and not just as the owner and manager of “The Franklin House.” Billy and his brothers fought for the South during the Civil War. He was a revered Confederate veteran, a cavalryman who rode under the now-infamous Nathan Bedford Forrest, as part of the 2nd Kentucky.

Like many southern men of his time, Billy came home from the war defeated and demoralized. Not only had he lost his brother, Robert, in the Battle of Franklin, but the victorious North saw him as a traitor to his country who sought to perpetuate the immoral institution of slavery. Yet, like many southern families, the Bringhursts refused to accept such an interpretation of their lives. They would nurse their wartime losses and seek to rehabilitate their image and their “Lost Cause” vehemently. Lulu became intimately entangled in this process.

“The United Daughters of the Confederacy” was created in 1894 and it did not take long before chapters of this growing group popped up in cities and towns throughout the South. The women of the UDC had a specific narrative they sought to perpetuate about the South and the Civil War.

Chapters held regular meetings and memorial services which mostly consisted of the sharing of stories from the war, both the men who fought for the Confederacy and the women who strove to survive at home. The perspectives or history of those who were freed from slavery was not included.

The women of the UDC also raised large amounts of money to erect monuments throughout the South both memorializing and glorifying Confederate veterans as well as working to provide care for those same veterans as they age.

Most members of the UDC were women of considerable social standing who came from families of wealth and influence. They used these tools to raise money for monuments, but then also to do something else of great importance to them. They became extensively involved in influencing the history curriculum taught in schools. They wanted to ensure that children were taught about the Civil War and slavery from their point of view. Only materials that portrayed an idyllic life prior to the war with happy slaves and southern soldiers who were honorable patriots were allowed.

One of their main points was to assert that the Civil War was not about slavery, but instead a simple constitutional disagreement about “states’ rights.” They wanted all of the children of the South to be taught this perspective. Prior to the Civil War, almost 4 million people were enslaved throughout the South.

Many original documents conflict with the UDC’s perspective. The constitution of the Confederate States of America states, “In all such territory, the institution of negro slavery as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected by Congress.”

Also, each southern state that seceded from the Union created declarations that stated their reasons. For example, the state of Texas claimed its reason was, “maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery–the servitude of the African to the white race…a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.”

Even though the Confederacy’s goals of maintaining white supremacy and the institution of slavery were clear, the state’s rights argument remained prominent in the school curriculum partially due to the work of the UDC.

Clarksville’s UDC – In Their Own Words

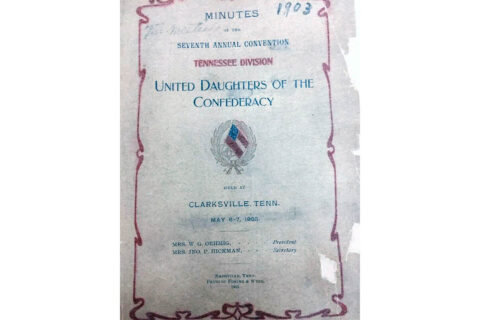

How do we know that Lulu and the UDC women of Clarksville continued to share white supremacist beliefs? They left records of their speeches at meetings and conventions. For example, Clarksville hosted Tennessee’s UDC state convention in 1903 at which there was a focus on white supremacy and racial purity.

Local historian and professor, Dr. Minoa Uffelman, shares and interprets these records in her new article, “United Daughters of the Confederacy: Progressivism ‘In Perpetual Remembrance’’.”

She writes, “Tennessee women were at the forefront of maintaining a racial hierarchy. The seventh state convention, hosted in Clarksville, was held at the Montgomery County courthouse … The president of the local chapter, Grace Stacker, welcomed attendees by telling a joke in black dialect. Then she explicitly stated the goals of white racial purity and the importance of ensuring African Americans’ continuation in racial subjection. Stacker declared, “Southern women stand together forever for the purity of our Caucasian blood against any encroachment from any source whatsoever that shall tend toward social equality with a race inferior to ourselves.” She continued, “For in so far as we shall be able to inspire them with the ambition to be faithful, conscientious and self-respecting servants in that station that God appointed them…”

Clarksville’s Confederate Monument

Lulu and her family were also instrumental in having Clarksville’s Confederate monument funded, created, and installed with much fanfare in Greenwood Cemetery in 1893. Clarksville’s monument was particularly important to her family since the sculptor modeled the soldier at the top after her father, Billy Bringhurst.

The local newspapers of the time were full of coverage surrounding such events. They also reported on the UDC meetings and ceremonies, as well as the many soldier reunions, but what is missing are the perspectives of Black members of the community.

They knew what the goals of the Confederacy were and what the monuments meant. They daily worked side by side in the community with families such as the Bringhursts. One wonders what the women who were cooks and maids in Lulu’s hotel thought about her UDC meetings? Did they feel their dignity trampled upon? Their voices are absent in the archives.

If the Black men and women in Lulu’s life had spoken out and disagreed, they would have faced repercussions. Sometimes repercussions were carried out by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, another group to which Lulu’s family had ties.

Lulu’s Family and the KKK

Lulu’s mother, Sallie, had her own story to tell about the Civil War. Remarkably, Sallie had lived in Pulaski, Tennessee during the war and shortly thereafter. Pulaski, Tennessee has become widely known as the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1907, Lulu wrote an article for the Nashville American newspaper to proudly share the story of her mother’s involvement. She wrote that Sallie was “…familiar with the origin of the Ku Klux Klan and was personally acquainted with the five young men who gave its birth.” Sallie herself shared that, “Calvin Jones of Pulaski originated the name….and organized the first clan in 1866 and I was let in on the secret, along with other girls in order that we should make the regalia. In the strictest secrecy, we went to the attic with bolts of red and white goods and made figures of skulls and crossbones, crosses ….which we sewed or pasted on the garments for the men and the horses. We were told in a mysterious way that whoever was up at midnight would see the strange sights and when that hour came we were up watching…..horsemen robed in these garments began to pass the house silently. They had skulls on sticks, with candles in them and other hideous emblems…The Negroes were panic-stricken by the Ku Klux Klan….they thought the Ku Klux Klan were the ghosts of their masters who had been killed in the war.”

Lulu’s mother helped sew the first costumes of the KKK in 1866 which would then terrify, oppress, and lynch Black citizens for decades. While the group may not have started out to be violent, the family was publicly associating with it after it had become so.

How could Lulu support and promote the KKK and then at the same time advocate for women’s equality? During her lifetime, Lulu aided the oppression of one group while helping to liberate another.

As we ponder women’s history month, we can recognize that while many white women fought for a woman’s right to vote, they were also simultaneously upholding white supremacy.

Learning >From History

Lulu Epperson’s mindset should not be overly surprising. It was shared by many of our ancestors. They often fought for the rights and freedoms of the group they belonged to but failed to extend the concept of equality to others. Our nation’s founding documents proclaim, “all men are created equal,” but the rights inherent in equality were not extended to women, African-American slaves, Native Americans, and other minority groups.

Clarksville and its history are interwoven into this story. Like many cities across the South, the culture of our city is rooted in the legacy of slavery. Valentine Sevier brought slaves with his family when he arrived in 1790 as did other frontier families. By the time the Civil War arrived, approximately half of Montgomery County’s population was enslaved.

This is our past. What can we do differently?

First of all, we can fully recognize the truth of our history, even the parts that are ugly or make us uncomfortable. We can then commit ourselves to complete respect, representation, and inclusivity of all groups. By doing anything less, we too are complicit in continuing this legacy. We can choose to learn from history, in this case, Lulu Epperson’s choices.

Her choices affected our current circumstances, in both positive and detrimental ways. If anything, her life reminds us that right now we are creating the future of tomorrow, and that is a powerful opportunity.