Clarksville, TN – This fall, Dr. Marisa Sikes, Austin Peay State University (APSU) assistant professor of languages and literature, is looking at cultural significance of the undead in her class “Zombies in Popular Film and Literature.”

Clarksville, TN – This fall, Dr. Marisa Sikes, Austin Peay State University (APSU) assistant professor of languages and literature, is looking at cultural significance of the undead in her class “Zombies in Popular Film and Literature.”

The course examines the origins of these fictional creatures in the form of the early 20th Century Haitian zonbi on to the Americanized zombie, which has its roots in contagion-based apocalypse fiction.

“I developed a special topics course based around the zombie film,” Sikes said. “It came out of my personal interest in it. I liked horror at that point in my life as a genre, and I think the zombie is a malleable figure that changes a lot over the course of time. This makes it particularly suited to different interpretations.”

The course is structured to give students a chronological look at how the zombie has developed over time through literature and film. Sikes starts by examining where zombie lore comes from.

“We start historically by talking about Haiti, its history of slavery, and how the zombie is connected to those social anxieties and fears that developed in a formerly enslaved nation,” Sikes said. “We also talk about the deep-seeded and highly problematic labor practices implemented by the U.S. in 20th century Haiti. It was essentially forced labor to build infrastructure that Haiti ‘needed’ to protect American interests.”

Sikes has introduced more literature to the course, including William Seabrook’s The Magic Island, which, according to Sikes, is the first work to bring the zombie into popular consciousness.

“His writing is part travel narrative and part sensationalist exploration of Haiti,” she said.

The Haitian Zombie

Haitian zombie lore is different from what they show in the movies. According to a website by the University of Michigan titled “Haiti & the Truth About Zombies,” the word “zombie” comes from the Kongo word nzambi, which means “soul.” According to an article by Mike Mariani, the zombie myth appeared when Haiti (then known as Saint-Domingue) was a colony of France. Africans were enslaved to work on sugar plantations and suffered brutality under the hands of the French.

Death was the only release from relentless subjugation by the French, according to Mariani. Upon death, Haitian slaves believed they would be free in an afterlife known as lan guinée. Mariani says that slaves who committed suicide would be condemned to shamble around the plantations for eternity.

According to the Michigan website, in Vodou, “all people die in two ways—naturally (sickness, gods’ will) and unnaturally (murder, before their time). Those who die unnaturally linger at their grave, unable to rejoin their ancestors until the gods approve.” Souls can be controlled by a powerful sorcerer known as a book, who also controls their undead bodies.

“Zombie lore is sort of a Haitian tradition that’s been scooped up out of Haiti and dropped into the U.S. It’s picked up all of the fears of Americans,” Sikes said.

The Americanized Zombie

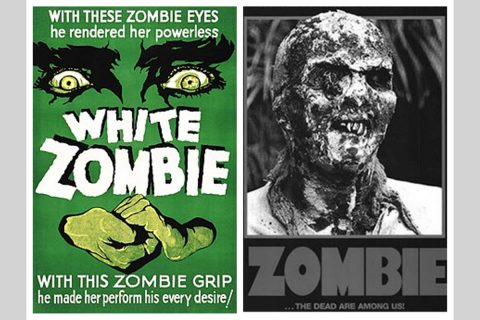

Sikes believes the zombie became more intertwined with American fears and unrest as it moved further away from its Haitian roots. The first feature length zombie movie, White Zombie (1932), figured that the best way to properly represent Haitian folklore was by casting Bela Lugosi, an Austria-Hungarian actor, in the role of the “evil voodoo master.”

“The film came out between the first and second world wars, so Lugosi is very feminized and portrayed as this ‘arch-nemesis’ to these ‘good American people,’” Sikes said.

White Zombie also contains blatant misogyny.

“White Zombie is a story about the fear of controlling white female sexuality,” Sikes said. “The horror is that, once she’s been turned into a zombie, she doesn’t have control over her chastity anymore. The tagline for the film is ‘she was not alive nor dead, just a white zombie fulfilling his every desire.”

Sikes continues, with heavy eye-rolling, “true love saves the day though.”

The film ends with the zombified woman recovering thanks to her husband and lives happily ever after.

Then came George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), which permanently changed the zombie in American consciousness. This was unintentional.

The film speaks to racial unrest in the United States, hatred, paranoia and groupthink. Most notably through its iconic ending.

“It’s all very reminiscent of lynching photographs from a book called Without Sanctuary,” Sikes said. “It’s a direct condemnation of that period in American history. If one looks at the still images and the end credits after Ben, the sole survivor of the night, emerges from the home and is shot on sight, the impromptu zombie posse presumably believing him to be a zombie, there is a distinct visual similarity between the shots of the bodies being tossed on the pyre and those found in Without Sanctuary.”

Challenging Horror Tropes of Women

Tom Savini’s remake of the film made in 1990, also written by George Romero, has a similar scene at the end of his 1990 remake in which the zombies are strung up in trees and shot for sport.

Savini’s remake also challenges common horror tropes for women. The best example of this is with the character Barbra. Sikes says in the 1968 version, Romero wrote her to be a “screaming, shrinking violet, who almost becomes catatonic.” In the 1990 version, Barbara is the main character and sole survivor.

“I screen Tom Savini’s remake from 1990 because it’s more progressive,” Sikes said. “It challenges the traditional horror tropes about women. The 1980s were dominated by slasher films. They often featured the survival of one girl — think of big franchises such as Halloween, Friday the 13th, and Nightmare on Elm Street.

“Savini’s remake is in part a response to the mousey presentation of Barbra in the original film,” Sikes continued. “She survives because she is the only one willing to leave the embattled farm house, realizing that the whole group could escape on foot and fight through them. The men in the film devolve into territorial bickering. Barbara then realizes the next morning, as the budding militias swoop in to exterminate the zombies, that the survivors are devolving into reckless violence.

“Through her eyes we see and critique the hysterical and masculine response to the zombies,” Sikes said. “As The Walking Dead anticipates, the real threat isn’t the zombies, it’s the people. That’s a modern interpretation of the zombie and not really associated with the Haitian definition of the zombie.”

Sikes believes the zombie’s relegation to a prop in apocalypse fiction is due to their insentience. Focus has shifted to the place of morals in a morally bankrupt world.

“Zombies, in and of themselves, are not going to carry the weight of the narrative because they aren’t sentient. You’re going to inevitably be drawn into the characters who are thinking and reacting,” Sikes said. “Most zombie films address the outbreak and the aftermath, but not so much the aftermath of the aftermath. That’s one of the reasons The Walking Dead graphic novel began. Robert Kirkman, the author, was interested in what happens to the character after the film ends.”

Tearing down social structures

Some films and books attempt to combine creatures and themes from different works to confront the audience with questions they will never be forced to answer. Those that are most effective, force us to put ourselves into the story, questioning our own morals.

One of the best examples of this can be seen in Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend. The story is about the last man on an Earth infested with rabid vampires. We come to question his motives as be begins dragging these vampires out of their dens and staking them during the day. It turns out, he is terrorizing a budding vampiric society that is similar to our own.

“What he doesn’t realize is that some of the vampires are sentient and have self-control. They aren’t just mindlessly seeking blood,” Sikes said.

Matheson challenges the idea of survival at any cost. It is this criticism that Sikes finds most appealing.

“What I enjoy most about good horror is that it tears down the social structures that are problematic in our culture and offers us creative solutions,” Sikes said. “What happens when you approach someone not with the perspective that they’re a vile human being, but you approach them with the perspective that they can be your partner, and you can build something with them. You approach them with respect. And they, they respond in turn with respect.”

It goes beyond flesh-eating zombies that entertain us as we snuggle up on a stormy October evening. It’s about the troubling conclusions we come to about ourselves, when the credits roll.

To learn more

If you want to read more about Haitian zombie lore, visit these links:

- “The tragic, forgotten history of zombies,” The Atlantic.

- “The truth about zombies,” University of Michigan.

To learn more about the Department of Languages and Literature at Austin Peay State University, visit www.apsu.edu/langlit.