Clarksville, TN – Great ships move through the early morning fog on the morning of June 6th, 1944 as the Allied invasion fleet heads towards the beaches of Normandy; it was D-Day, the invasion of Europe. More than 5000 ships were massed to carry the weapons of war to the newest front against the Axis powers. In addition to the battleships cruisers, destroyers, and the various troop transports of which you are most familiar from watching the various war movies of the landings , were 236 Landing Ship Tank (LST) vessels, including the USS LST-325 which is docked through Sunday at McGregor Park in Clarksville, TN.

“The LST’s were the workhorse of the Navy in both the European and Pacific campaigns back in World War II,” said Captain Robert D. Jornlin the Commanding Officer (CO) of the LST-325. “When the British got pushed off European mainland at Dunkirk by the Germans, they had to leave all of their equipment on the beach; and they were barely able to get all of their soldiers off in time. Even as they left the mainland in defeat; British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had not given up the fight and they knew that they would be back sooner or later,” he said.

“So, as the British were getting pushed off they had already began thinking about what it was going to take to get back onto European soil, when the time came to defeat Hitler. They began planning for ships that could go into a raw beach without any facilities, because Germany was certainly going to have all of the ports and harbors mined and heavily fortified,” he continued. The reason that is significant was that up until that time, most ships needed a crane and an dock to go to in order to unload its cargo. “Churchill wanted ships that did not need those type of facilities. So LST’s were a secret weapon when they first came out.” The ships, the British eventually produced failed in their mission; because they had a V-bottomed hulls, and lacked a gradient, “They were 9 feet at the bow and, they were 9 feet at the stern,” Jornlin continued.

Winston Churchill, then conveyed to President Franklin Roosevelt the need for these ships, and American’s naval planners soon got to work.

LST-325 is the perfect example of the ships they produced. She is a total of 328 feet long, and is 50 foot wide. The ship has a rake of 1 foot in 50 feet, “which is the gradient of the average beach,” Jornlin explained. The LST’s displaced 2,366 tons, and could could carry a 2,455-ton load of tanks, vehicles, and other supplies. When configured for a beach landing LST-325 draws about 3-1/2 feet of water at the bow, and 9 feet at the stern. “We have a flat bottomed hull so the ship to go right up into the beach, and the bow won’t dig in, like the English ships did,” said Jornlin. The ship had a crew of 10 officers and 100 enlisted sailors; and had additional berthing facilities for 300 additional troops. The ship also carries two Landing Craft, Vehicle Personnel (LCVP); or Higgins boats. The ships were armed with a variety of weapons which could include a mixture of 40mm or 20mm gun mounts.

The ship is powered by Two General Motors 12-567, 900 hp diesel engines , which provides power to two propeller shafts, with a top speed of 12 knots, and could travel 24,000 miles at 9 knots while displacing 3,960 tons. Electricity is provided by onboard generators. In the engine room a maze of pipes transport fuel, compressed air, and water throughout the ship. Each engine had its own engine telegraph, which provided instructions from the bridge to the engine crew.

Another American innovation was the addition of a 3000 pound Danforth sand anchor on the back with 600 feet of cable. Since LST’s go into the beach pretty fast, they would drop that anchor 900 feet out. This anchor does two things. “It keeps you from broaching, keeps you straight,” said Jornlin. “Then when you get everything off the ship, you pull on that anchor and back your engines and off the beach you go.”

The ship typically carried a Landing Craft Tank (LCT), tanks and other vehicles including artillery, construction equipment and military supplies both in an internal cargo hold, and on the upper deck. A ramp or elevator forward provided the ability to move cargo from the main deck to the tank deck. Many LST’s also carried sectional pontoons attached to the sides of the vessel amidships, to either build Rhino Barges or use as causeways. Married to the bow ramp, the causeways would enabled payloads to be delivered ashore from deeper water or where a beachhead would not allow the vessel to be grounded forward after ballasting.

They made 1,051 LST’s during the wars. They were putting one out out every five days in shipyards located in Evansville, Indiana;Seneca, Illinois; Jeffersonville, Indiana; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania which had 2 shipyards.

Let’s get back to Capt. Jornlin. “So the LST was very instrumental, as like I said it was kind of a secret weapon because they really didn’t want Germany to know that they want to make an invasion at one the ports, they were going to go into a plain bare beach somewhere, such as Normandy,” he said.

A total of 25 LST’s were used in the Vietnam conflict.

After the Vietnam conflict LST’s were mostly decommissioned, with a few being transferred to allied countries, including the Philippines, and Greece. This included the LST-325, which was transferred to Greece and renamed the Syrios (L-144) where it seved until 1999.

In 2000 the LST-325 was acquired by U.S. LST Ship Memorial Inc. and made ready for an epic 5,000 mile voyage back to the United States. The account of that journey written by Captain Jornlin is included here in full with his permission.

I became involved with the U.S. LST Association (a group of approximately 10,000 veterans who served on LSTs during the wars in which the U.S. participated). We were trying to find an LST (Landing Ship Tank) World War II ship so that people in the U.S. could go to see as a museum. We found out that there weren’t any. The U.S. Government had given them all away, or sold or scrapped them.

We started looking in foreign countries to which the U.S. Government had given the ships. Taiwan had 23, Brazil had a couple, and Mexico and the Philippines had some. We never thought about Greece, but they had 6 or 7. We went to Taiwan in 1990, but that did not work out. Then, in 1995, one of our crewmen by the name of Ed Strobel visited some friends in Greece. They have a program in Greece, a treaty with other Mediterranean countries, that they can only have so many ships. If they built one or got another one, then they had to take some out of commission to keep the numbers the same.

The Greek Government said they were going to take the old LSTs the U.S. had given them after the war and moth-ball them. Ed said that he was a member of a group that would like to have one, and asked if we could have one. His friend said he would look into it. After a while, the Greek officials said that they would be glad to give the LST Memorial a ship for a museum, as long as our Government said it was O.K. In 1999, the U.S. approved it.

Some members of the LST Association went over to Crete in March, 2000 and looked at the ships. The Syros L-144 (the name the Greek Government gave the LST) was the one we chose because it had been dry docked in December of 1999, and came out of dry dock in January of 2000. There had been a lot of work done on it, and the hull seemed to be the best of all of them. Cosmetically, on top, it was not the best, but we were looking for the best hull. Things were stalled until July of 2000, and then we went back over to Crete. They had continued to take parts off the ship, so we had a ship that was not in as good shape as we had hoped it would be, and was not ready to sail as quickly as we thought it would be. It took about three and one-half months to get that ship back in shape and ready to go.

Everyone chosen for the crew had to take a refresher test on basic information, seamanship, first aid, firefighting … most of the things needed to be a member of this crew. We also had to take a CDL (commercial driver’s license) physical. I had a couple of guys who had taken that test in 1995, and then neglected to do it within six months of their going over to Greece. So, we had some guys who were not in the best of health, and should not have gone.

Everyone had to come up with $2,100.00 to pay their own airfare. We had donations to the LST Memorial, but at that time, we did not have very many. The requirement was that you pay for your own flight and come up with the $2,100.00 to pay for fuel and food. British Petroleum Oil Company donated 50,000 gallons of fuel for the voyage from Greece to the U.S., which really saved us.

There were 72 guys on the crew list, but only 61 or 62 went over to Greece, and quite a few of them did not stay. Some left after two weeks. There was lots of paper work to complete and they had to give Power of Attorney on health care to a ship’s officer so that in case something happened, we could make a decision. We sent several men home because of health reasons. One died of a heart attack at JFK Airport on his way back home. He had previously had two heart attacks and should not have gone on the trip, but he wanted to do it so much. I talked some guys out of going over to Greece who were having trouble breathing. I told them, if you are having trouble breathing here, going over there with the 100-degree temperatures would be crazy. Some of the men who went over ended up in the hospital. The doctor told me that I should send them home, and I did.A lot of the original men who went over to Greece thought it was going to be like a Caribbean cruise. In WWII, they had been on a new LST, and this ship was far from new, and they had forgotten how uncomfortable those ships were. When we did not sail immediately, they went home. I would get replacements, and they would ask when we were leaving. I told them maybe in two weeks or a month. If the sailing time went a couple of days beyond what I said, some would go home. The final crew consisted of 28 dedicated men. The 29th man was a photographer I took on at the last minute, because he wanted to go and I was short of help. He was about 40 years old, from Up-State New York, and worked for National Audio Video, who was doing a documentary for us. I told him “No” three times. Then I started thinking about it. I did not particularly want camera people taking pictures of everything we did. We had enough problems getting things done without someone in our way, but we needed help. He paid his money, stood watch for us, and took pictures on his own time. He was really good about it. I told him he could not get in anyone’s way, and that he couldn’t take any bad pictures of the Captain!

I did not go over to Greece until August 28, 2000, arriving in Crete on August 30. Before I left the U.S., I called over there and the guy who was in charge told me that the ship was 80% ready to go and that we would sail in six days. He told me to bring the rest of the crew. I had planned to bring another 30 guys, but actually, 28 went with me. The ship actually was about 1% completed … certainly not 80%!

The American Embassy in Greece called me in for a conference as soon as I arrived, and told me that if I did not send the guy who was then in charge of the LST project back to the U.S., they were going to pull their support. He had ruffled a lot of feathers. I had a hard task, and did not look forward to this, but the man in question made it easy for me. I went to him on that first day of my arrival and said “You know, you are ruffling everybody’s feathers and they are kind of mad at you. You have got to let me handle the men and the Greeks and the Navy and State Department. You can do what you do best, and that is to repair the engines and get things ready to run.” He said, “Well, we’ll try it.”

The next day, the Navy guys from the U.S. Navy Base at Souda in Crete were on board the LST, and they had put a reefer in the wrong place. The guy who was originally in charge came and told me that it had to be moved to a different location and that if it was not done immediately, he was going to walk. I said “I am not going to ask these Navy guys, who had worked very hard as volunteers to get this thing where they had put it, to move it. Let them go back to their base, and the crew and I will get it moved after they leave.” He said, “Nope, they gotta do it right now, or I am leaving.” I said, “Well, it is not going to get done right now.” So, he packed his bag and left, and nobody shook his hand or said goodbye to him … that is how mad they were at him.

The crew was great. They were the ones responsible for the success of this project. They made my job so easy that I almost felt bad having it. I joked and said that I couldn’t do anything, so they made me Captain. I had a lot of talent on that ship. About one half of them were WWII veterans, and the other half were veterans from the Korean Conflict. I had an electrician who had worked all his life in the electrical business. I had an engineman who had a very successful company that manufactured overhead doors for semis, and one guy who worked for Libby-Owen, making windshields for 43 years. All of the guys on my crew were experienced and successful. Guess they had to be to afford the $2,100.00 airfare, and then they had to pay their own expenses

for all that time over in Greece. We had two meals on the ship, but if they went ashore and bought a meal or a beer, it was their own expense. Before the ship was ready for us to get on, the crew had to buy all their meals.After the months of getting the ship ready to sail, we left Crete on November 14, 2000. We stopped in Athens for supplies. After we left Athens, we lost an engine. We had a manifold that cracked and let water down into the cylinders, so we could not run that engine at all. Crossing the Mediterranean took us 13 days instead of 9 days. We also lost our steering and lost a gyro. So, we kind of limped into Gibraltar and had everything repaired (that took 12 days) and headed back out to sea. We had gone about 1,000 miles and we lost an injector in the #12 cylinder, and it burned the piston and the lining. We had to shut that cylinder off. That engine ran for 3,000 miles with just 11 cylinders.

We had some stormy weather. The wind was out of the West coming across the Med and the Atlantic, so it was always blowing against us. We would have liked an Easterly wind.

We were scheduled to arrive in Mobile, Alabama on January 10, 2001. We had started the journey from Greece on November 14, 2000. We did arrive on schedule in Mobile. We knew our families were going to be there, but we had no idea that there were thousands of people from all over the U.S. there to see us come in. Plus, the Mobile newspaper and television stations had really done a good job. For weeks in advance, they had run daily reports on our progress. They made this thing into a real epic voyage.

We went into the post office in Mobile to mail some items, and the guy in the back of the post office yelled to the lady waiting on us and said, “You know who you have there?” She said, “No.” He said, “You have the Captain off of the LST.” We had been waiting in a line of people. She wanted an autograph, and some of the people in the line also wanted an autograph. It kind of embarrassed me. I don’t know how you get used to that type of thing. For some reason, we have touched the hearts of veterans and older people. I have had a lot of phone calls from guys from WWII who served on an LST and guys from the Korean War who just want to talk to me.

We never figured on this being anything great or heroic. All of us guys just wanted to bring back an LST. We think the LST has been very underrated and unappreciated as far as the importance it played in the different wars. We wanted one so that we could all go aboard and remember the days we were on them, and so that our children and grandchildren would also be able to see an LST. That was the sole purpose of doing this. We never thought this thing would attract so much attention. We are happy that it happened, and we hope we can get some donations and keep it going. The plan is to keep the LST-325 running and move it around so that other people will get to see it.

We need funds to refurbish the ship, and anything that can be given will be very much appreciated. We have a program wherein if $100.00 is given, the donor will receive a hat and T-shirt. If $1,000.00 is given, the donor will receive a plaque and a hat and T-shirt. Depending on certain larger amounts donated, a stateroom on the ship may be named after the donor, or in honor of someone the donor designates.

As you can see it was quite a trip. The U.S. Coast Guard at the time recommended against the trip for safety reasons. “Last week a Coast Guard marine safety officer questioned the adequacy of the vessel’s lifesaving equipment & also found it lacked an emergency electricity generator. In his letter, described in a Coast Guard news release December 6th, Admiral Shkor said that if the LST-325 were a commercial vessel he could order safety repairs. But since it is not, he could only recommend that the ship be towed back or that it be repaired before sailing.” recounted an article at the time on the Cargo Letter Web Site. But they successfully made it home to the United States.

The History Channel made a documentary on the Journey, this is a short clip from it. The full length video is available in the gift shop on board.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWe9qaMR2rI[/youtube]

The ship is open for tours through Sunday from 9:00am till 5:00pm, come out and meet these amazing men and tour this wonderful ship. Tours are roughly 45 minutes long and include the Main Deck, Troop Berthing, Tank Deck, Mess Deck, Galley, Aft of ship (Guns and Anchor), Wheel House, Officer’s Country and the Captain’s Cabin. It includes 3 sets of stairs down and 3 sets of stairs up. You are allowed to ask questions and take pictures at any point during the tour. You should wear good walking shoes, heels of any type are not advised. During the summer we also recommend carrying water during the tour (available in the Gift Shop) due to the increased temperatures onboard ship. The ship is fully operational, and all tours are guided.

Admission is $10.00 for adults, $5.00 for children. A family pack prices available for $20.00. Active duty soldiers in Uniform are admitted free. The money help goes to fund the operational expenses of the ship. All of the crew are volunteers.

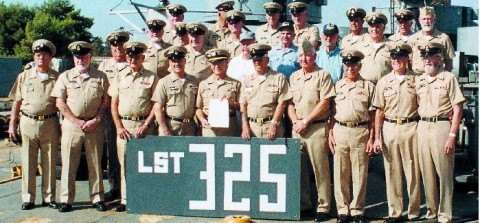

Photo Gallery

The history of LST-325

The keel for LST-325 was laid down on August 10th, 1942, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Philadelphia, PA. 48 days later she was launched on October 27th, 1942, sponsored by Mrs. G. C. Wells. The ship was commissioned the USS LST – 325 on February 1st, 1943, with Lieutenant Ira Ehrensall of the United States Naval Reserve in command.

The keel for LST-325 was laid down on August 10th, 1942, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Philadelphia, PA. 48 days later she was launched on October 27th, 1942, sponsored by Mrs. G. C. Wells. The ship was commissioned the USS LST – 325 on February 1st, 1943, with Lieutenant Ira Ehrensall of the United States Naval Reserve in command.

She crossed the Atlantic a month later as part of the first convoy of U.S. Navy LSTs to reach the European war zone. The ship was assigned to the European theatre and participated in the invasions of Sicily, Salerno, and Normandy. She also participated in other operations along the northern coasts of France.

In March 1945, LST-325 crossed the Atlantic from Belfast, Northern Ireland, to the U.S. Overhauled at New Orleans, she was fitted with Brodie gear for launching and recovering light observation airplanes. She briefly exercised with that equipment in August 1945, just before Japan’s surrender ended World War II. She made a trip to Panama in September-October of 1945, and was decommissioned for the first time on July 2nd, 1946, at Green Cove Springs, Florida. The ship was placed in the Atlantic reserve fleet where she stayed until 1951.

In 1951 the ship was placed back into service with the Military Sea Transportation Service as USNS T-LST-325. She was given a reinforced bow to better suit her for work in icy waters, and took part in “Operation SUNAC” (Support of North Atlantic Construction), venturing into the Labrador Sea, Davis Strait, and Baffin Bay to assist in the building of radar outposts along the eastern shore of Canada and western Greenland.

The ship was decommissioned for a second time and struck from the Naval Register on September 1st, 1961 when it was transferred to the Maritime Administration (MARAD) for lay up in the National Defense Reserve Fleet.

Two years later, in September of 1963 the ship was reactivated by the Navy, and was modernized for further use under the Military Assistance Program . She was transferred to Greece in May 1964. The Greeks renamed the ship RHS Syros (L-144) and operated her for more than three decades. Syros left active service in the later 1990s.

Two years later, in September of 1963 the ship was reactivated by the Navy, and was modernized for further use under the Military Assistance Program . She was transferred to Greece in May 1964. The Greeks renamed the ship RHS Syros (L-144) and operated her for more than three decades. Syros left active service in the later 1990s.

The ship was acquired in 2000 by the USS LST Memorial Inc., a Pennsylvania not-for-profit corporation, and renamed M/V LST-325. Manned by 29 members of the USS LST Memorial Inc., she sailed from Greece in December 2000 setting a course for Mobile AL., She arrived, January 10th, 2001 at Mobile. Redesignated as Historical Museum USS LST-325, early 2004. LST-325 serves as a tribute to all LST sailors. Her home port is Evansville, Indiana.

USS LST-325 earned two battle stars for World War II service