Written by D.C. Thomas

Clarksville, TN – Following the publication of Part I of my feature on Maestro Igor V. Babailov, I now invite readers to step further inside the artist’s world, not into a second visit, but deeper into that first unforgettable experience as I walked through the halls of his Brentwood home and into his private studio.

Clarksville, TN – Following the publication of Part I of my feature on Maestro Igor V. Babailov, I now invite readers to step further inside the artist’s world, not into a second visit, but deeper into that first unforgettable experience as I walked through the halls of his Brentwood home and into his private studio.

In the bright foyer that connects multiple rooms, on the wall alongside the staircase, a portrait of his wife holds a central place.

Dressed in an elegant pink gown, she stands beside their beloved pet.

The towering standing portrait, The Baroness, Mediterranean Nights, reflects her heritage.

“This is a portrait of Mary,” he told me. “That is Chester. Unfortunately, he passed away recently, but the background of everything is entirely from my imagination. I wanted to incorporate that Mediterranean feel, that connects to her heritage, to her background. Her grandmother was a baroness from Italy, so I wanted to create that regal look and Mediterranean look at the same time.”

As we moved past portraits and carefully placed memories, the Maestro guided me toward a space that felt set apart: his studio. There, surrounded by works known and not yet shown to the public, I encountered what most never see: the tools behind masterful art. Resting nearby were his palette and brushes, along with the palette once used by his father. Tubes of paint, still in use, gave evidence of a working artist who continues to uphold a centuries-old discipline with every stroke.

It felt deeply moving to witness the physical instruments that, over time, have helped shape the images of presidents, popes, and historical figures.

In another room, adjacent to the foyer, I locked eyes with a collection of vintage hand-painted Russian lacquer boxes. Above them, there it was: “The Resurrection of Realism”, the original artwork that draws one’s soul in. Nearby, in a glass display, the awards and papal rosaries he had received from the three popes he painted. These symbols of recognition stood as graceful reminders of the work and reverence poured into every artwork by the Maestro.

Throughout the steps we took together in his house, the Maestro discussed his dedication to traditional art education and the importance of drawing from life over relying on photographs.

He shared his experiences and said that there are challenges to maintaining artistic integrity in a digital age.

“I know, human nature can make you lazy… You know, all these gadgets,” he said, referring to shortcuts that tempt artists away from skill development. “You have to be an example for your students. You have to teach them.”

Here the Maestro mentions Leonardo Da Vinci, who “was as innovative, as he was a genius” and he said that even though one might be tempted to use the camera because it’s available he is confident that Da Vinci would never have given into this temptation, or to the gadgets and computers when it comes to paintings and sketching from life or en-plein air. And that he would still work in the same way as Michelangelo and their contemporaries, as they had continued to work on their self-discipline and self-improvement.

Further, he explained that even when time is limited, he requests a live session to create a drawing. “I always have a seating with a person. I request a seating… so I can draw them. Because with drawing, you can do it much faster. But my goal is to capture the likeness of the person, in those minutes that they have… Because that will also give them confidence in who they deal with.”

“When I travel, when I go somewhere, I have a pencil and sketchpad. I don’t need to take some equipment,” he said, emphasizing his reliance on fundamental skills and discipline rather than technology.

He also described the experience of painting en-plein air: outdoors and on location. “Even when you go to paint en-plein air… plein air means painting outside. Everything is changing. Every second. The weather changes… not to mention that if it’s a sunny day, everything changes. The shadows change, the Sun moves… It’s a challenge to work faster, it forces you to work faster, to think fast… It requires skill. …Like those of the Old Masters.”

And so, the Maestro does not rely on photographs when creating a portrait. “A photograph can distort your proportions… That’s what the camera does. That’s why I never copy photographs,” he said. Instead, he may consult multiple reference images to understand the subject’s anatomy, but insists on maintaining artistic integrity through draftsmanship and observation.

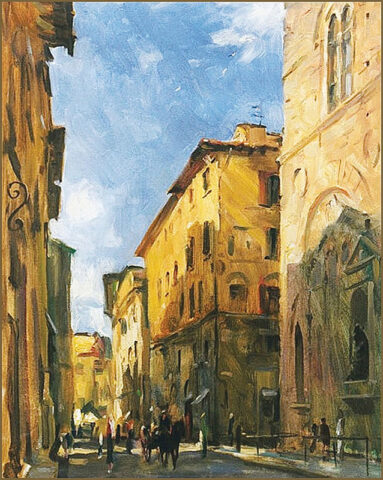

Near the end of our time in his home studio, I took one last look at his plein air works from Europe, hanging in the foyer. I had to say goodbye and revisit now through memories.

“I didn’t limit myself to just painting portraits… I like to paint everything,” he said to me. “I am known as a portrait artist, probably because of all those famous people. But I paint landscapes from life, entirely from life… each one of them took three and a half hours,” he shared.

His recently released book, Legacy Portraits, offers a rare and beautifully curated window into that legacy. Featuring over 100 selected portraits, the volume chronicles Maestro Babailov’s professional encounters with people from all walks of life: private individuals, presidents, Supreme Court Justices, prime ministers, royalty, three Popes for the Vatican, and more.

Legacy Portraits is a masterwork in itself: a testament to his philosophy, his process, and his unwavering dedication to the classical tradition. Readers who wish to explore the breadth and beauty of his work may consider ordering the book and visiting his website for further insight into the world of a living Master.

With conviction, Maestro Babailov once again reminded me that being an artist is not merely a career, it is a mission. A calling. And a legacy.

For more information about Maestro Igor Babailov visit www.babailov.com