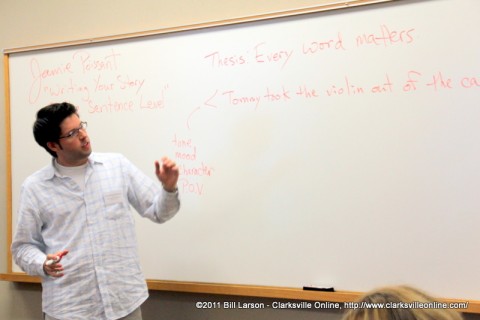

In a room full of writers, many of whom could be described as seniors, one gentleman quipped, “Are we sure this guy is old enough to be teaching a class?” when David James Poissant took over the microphone at the Clarksville Writers’ Conference.

In a room full of writers, many of whom could be described as seniors, one gentleman quipped, “Are we sure this guy is old enough to be teaching a class?” when David James Poissant took over the microphone at the Clarksville Writers’ Conference.

No matter how young he looks, Poissant has a history of publication that any writer would prize. His stories are published or will soon be appearing in places like The Atlantic, Playboy, The Southern Review, Mississippi Review, The Chicago Tribune, The Greensboro Review, and One Story. He has won the Playboy College Fiction Contest, The George Garrett Fiction Award, the AWP Quickie Contest, and second and third prizes in the Atlantic Monthly Student Writing Contest. His stories appear in New Stories from the South 2008 and Best New American Voices 2008 and 2010.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fXe5aidJ2Bk[/youtube]

Currently a Ph.D. candidate and Taft Fellow at the University of Cincinnati, he joins the MFA faculty at the University of Central Florida in Orlando this fall.

Poissant who introduced himself as “Jaime” proved himself well up to the task of teaching other writers about short story writing as he went through not only the elements of a story but dissected Lorrie Moore’s short story, “Dance of America” (from Birds of America: Stories) with organized and easily understandable expertise.

To encourage Beginning with the elements of story–plot (conflict), character, setting, dialogue (including dialect), and point of view (voice)—Poissant briefly described each.

“Plot is roadblocks,” he insisted. “Point of view is how we are informed by what the character wants.”

Diametrically opposed to the way Amy Greene began her prize-winning novel, Bloodroot, Poissant taught that to write a short story, “Character isn’t something you should start the story with. It’s what happens when plot meets point of view. Many tips tell you to describe the character. But that’s not where to start.

“Until you know what’s going to happen, you don’t know how your character will react. You’ll be stuck if you decide who the character is before you see what’s going to happen,” he concluded.

The two kinds of characters are those that are round (someone who is developing in the story) and stereotypical (flat personalities that do not evolve during the story), according to theory taught in most writing classes.

Jaime said that you must show a character through how he or she acts. Action defines a character. Characters must not be perfect. Don’t be afraid to give them flaws. Vulnerability is what makes the character human.

Jaime said that you must show a character through how he or she acts. Action defines a character. Characters must not be perfect. Don’t be afraid to give them flaws. Vulnerability is what makes the character human.

In addressing point of view—first person “I,” second person “you,” third person “he”, “she,” “it”—you need to keep in mind that the easiest is first person, he continued. “In first person, you are in the mind of the character. Second person is the hardest and there aren’t too many good examples of this. Third person is the trickiest. You have an omniscient narrator or a limited omniscient and you have to decide how close you want that person to be.”

Ultimately, in Poissant’s opinion, if you have a lot of characters, you’ll need to choose third person. Point of view determines what the story looks like.

Because plot is the most important in how to structure a story, you’ll need to know two things: (1) All stories need a beginning, middle, and an end that is surprising but inevitable; and (2) conflict is essential. Jaime said that in the story of Eden, if the snake never shows up, all you have is naked people petting lions.

He went on to relate that tension provides the opportunity for change. Characters have to have the opportunity for change. They have to be faced with the opportunity to change and decide whether or not to make that change. They have to be forced to look at themselves through conflict. It doesn’t have to be life or death. It just has to be a pivotal change. Emotion beneath the surface can make this happen.

One of the methods of providing the bones of a story is to make the plot evolve into a triangle: introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, end.

“Usually when you hit the climax, it’s nearly over,” Poissant taught. “Either the character gets or doesn’t get what he wants. You can also think of the story as a circle. The ending must be surprising and inevitable.”

Readers don’t want to feel lost, according to Jaime’s way of thinking. “They need to know who, what, when, where, why, how. When you are writing a story, you are in the present but you always have to address the past.

Poissant read parts of “Dance in America” and had members of his class read others. Dissecting Lorrie Moore’s short story, he said that the author shows who the characters are and that they were close because they have immediate repartee that is witty and quick.

Jaime’s directives are to enter a scene late, get out late, and “skip the door.” You don’t have to describe the character walking to the door, entering the door, etc. Give the highlights. Skip the boring parts. Less is more! If you spend a page in prose only or dialogue only, cut some of it.

Describing the “Dance” story, he said that pages one to four are the beginning as they set up everything we need to know. Pages five to 10 are the middle of the story. Usually the middle is about as long as the beginning and the end put together.

Quoting Frank Conrad, Poissant said, “Think of the story as climbing a mountain. You are picking up a rock on the way up. If you get to the top and still have a rock that you don’t need, you’ll be unhappy.”

Quoting Frank Conrad, Poissant said, “Think of the story as climbing a mountain. You are picking up a rock on the way up. If you get to the top and still have a rock that you don’t need, you’ll be unhappy.”

Editing is critical to the success of the short story. “Often I write stories of 40 or so pages and cut them to 25 at the end,” Poissant concluded as time ran out.

In order to fully understand his critique of Lorrie Moore’s “Dance in America,” it will be necessary for you to view the video of the class; it is attached to this article through the efforts of Mark Haynes.

It is well worth watching.