Written by Karen C. Fox

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

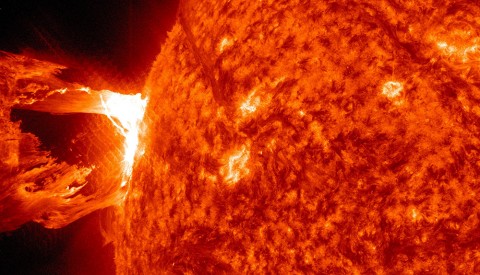

Greenbelt, MD – The sun’s atmosphere dances. Giant columns of solar material – made of gas so hot that many of the electrons have been scorched off the atoms, turning it into a form of magnetized matter we call plasma – leap off the sun’s surface, jumping and twisting. Sometimes these prominences of solar material, shoot off, escaping completely into space, other times they fall back down under their own weight.

Greenbelt, MD – The sun’s atmosphere dances. Giant columns of solar material – made of gas so hot that many of the electrons have been scorched off the atoms, turning it into a form of magnetized matter we call plasma – leap off the sun’s surface, jumping and twisting. Sometimes these prominences of solar material, shoot off, escaping completely into space, other times they fall back down under their own weight.

The prominences are sometimes also the inner structure of a larger formation, appearing from the side almost as the filament inside a large light bulb. The bright structure around and above that light bulb is called a streamer, and the inside “empty” area is called a coronal prominence cavity.

“We don’t really know what gets these CMEs going,” says Terry Kucera, a solar scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD. “So we want to understand their structure before they even erupt, because then we might have a better clue about why it’s erupting and perhaps even get some advance warning on when they will erupt.”

Kucera and her colleagues have published a paper in the September 20th, 2012, issue of The Astrophysical Journal on the temperatures of the coronal cavities. This is the third in a series of papers — the first discussed cavity geometry and the second its density — collating and analyzing as much data as possible from a cavity that appeared over the upper left horizon of the sun on August 9th, 2007 (below). By understanding these three aspects of the cavities, that is the shape, density and temperature, scientists can better understand the space weather that can disrupt technologies near Earth.

The August 9th cavity lay at a fortuitous angle that maximized observations of the cavity itself, as opposed to the prominence at its base or the surrounding plasma. Together the papers describe a cavity in the shape of a croissant, with a giant inner tube of looping magnetic fields — think something like a slinky — helping to define its shape. The cavity appears to be 30% less dense than the streamer surrounding it, and the temperatures vary greatly throughout the cavity, but on average range from 1.4 million to 1.7 million Celsius (2.5 to 3 million Fahrenheit), increasing with height.

To do this, the team collected as much data from as many instruments from as many perspectives as they could, including observations from NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), ESA and NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the JAXA/NASA mission Hinode, and NCAR’s Mauna Loa Solar Observatory.

They collected this information for the cavity’s entire trip across the face of the sun along with the sun’s rotation. Figuring out, for example, why the cavity was visible on the left side of the sun but couldn’t be seen as well on the right held important clues about the structure’s orientation, suggesting a tunnel shape that could be viewed head on from one perspective, but was misaligned for proper viewing from the other. The cavity itself looked like a tunnel in a crescent shape, not unlike a hollow croissant. Magnetic fields loop through the croissant in giant circles to support the shape, the way a slinky might look if it were narrower on the ends and tall in the middle – the entire thing draped in a sheath of thick plasma. The paper describing this three-dimensional morphology appeared in The Astrophysical Journal on December 1st, 2010.

Using a variety of techniques to tease density out from temperature, the team was able to determine that the cavity was 30% less than that of the surrounding streamer. This means that there is, in fact, quite a bit of material in the cavity. It simply appears dim to our eyes when compared with the denser, brighter areas nearby. The paper on the cavity’s density appeared in The Astrophysical Journal on May 20th, 2011.

“With the morphology and the density determined, we had found two of the main characteristics of the cavity, so next we focused on temperature,” says Kucera. “And it turned out to be a much more complicated problem. We wanted to know if it was hotter or cooler than the surrounding material – the answer is that it is both.”

Ultimately, what Kucera and her colleagues found was that the temperature of the cavity was not – on average – hotter or cooler than the surrounding plasma.

While these three science papers focused on just the one cavity from 2007, the scientists have already begun comparing this test case to other cavities and find that the characteristics are fairly consistent. More recent cavities can also be studied using the high-resolution images from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which launched in 2010.

“Our point with all of these research projects into what might seem like side streets, is ultimately to figure out the physics of magnetic fields in the corona,” says Gibson. “Sometimes these cavities can be stable for days and weeks, but then suddenly erupt into a CME. We want to understand how that happens. We’re accessing so much data, so it’s an exciting time – with all these observations, our understanding is coming together to form a consistent story.”