NASA Langley Research Center

Hampton, VA – Chill out. That’s the current message from the Sun to Earth’s upper atmosphere says NASA.

Hampton, VA – Chill out. That’s the current message from the Sun to Earth’s upper atmosphere says NASA.

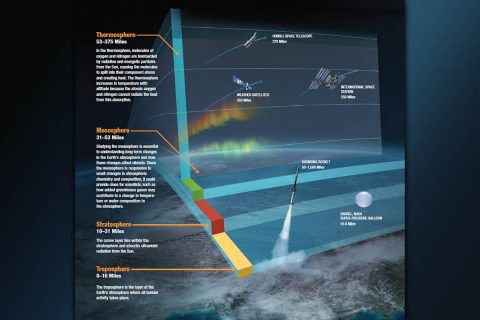

To be more precise, as the Sun settles into a cyclical, natural lull in activity, the upper atmosphere, or thermosphere — far above our own climate system — is responding in kind by cooling and contracting.

Could that have implications for folks down here on the surface? Absolutely not. Unless, that is, you’re someone with a vested interest in tracking an orbiting satellite or space debris.

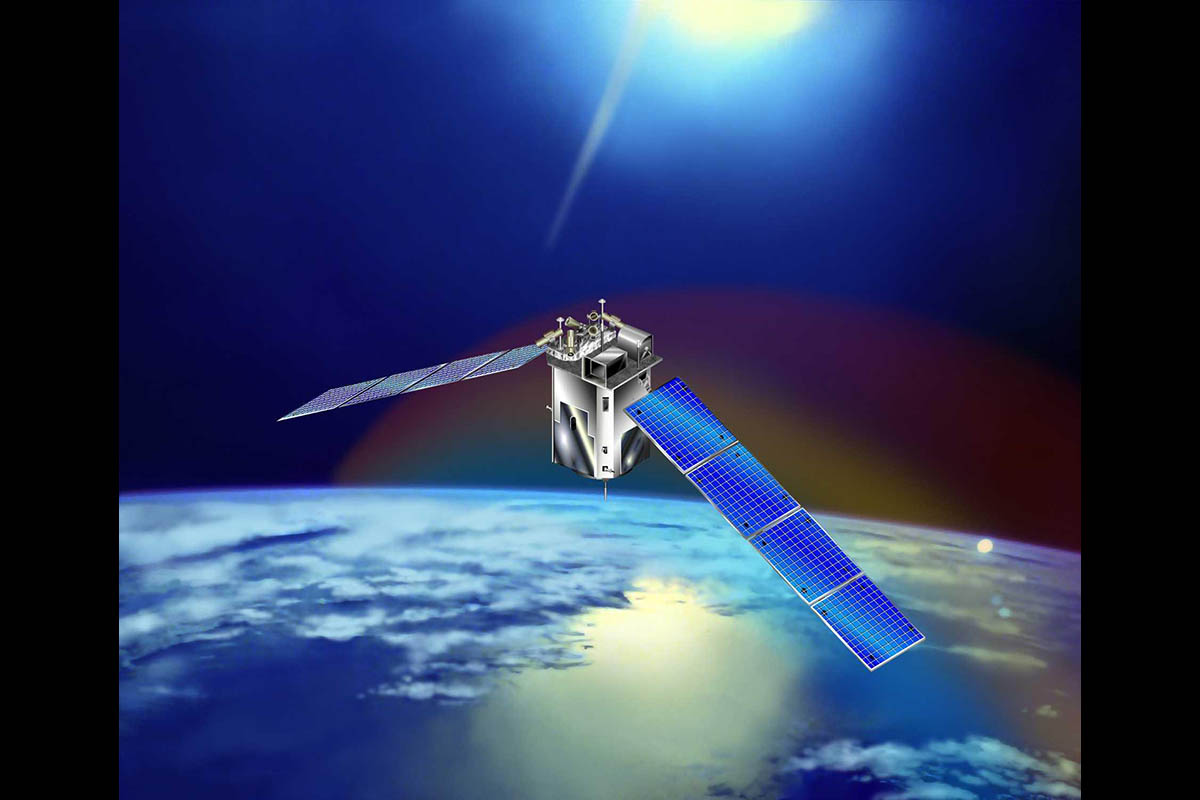

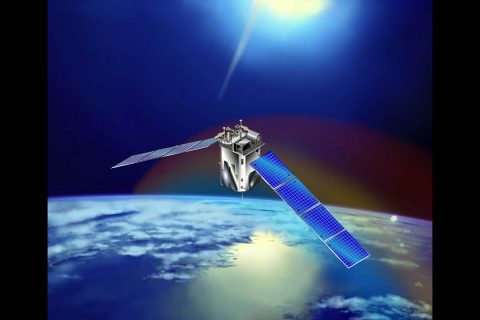

Beginning approximately 60 miles above Earth’s surface and extending out to about 375 miles, the thermosphere is where the Sun and the atmosphere first interact. When solar activity is low, like it is now, and the thermosphere cools and contracts, satellites in low-Earth orbit feel the effects.

“They encounter less drag and their orbits will not decay as much due to that. It’s good for satellites,” said Marty Mlynczak, a senior atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

To be totally clear, this cooling is natural and specific to the thermosphere. The cooling thermosphere does not affect the troposphere, the layer of the atmosphere closest to Earth’s surface where people live. The temperatures we experience on the ground do not get colder due to this solar cycle. NASA and other climate researchers continue to see a warming trend in the troposphere. These two effects are ongoing but unrelated.

Despite the warming trend close to Earth, the higher thermosphere is cool now because the Sun emits less extreme ultraviolet, or EUV, radiation during its natural lull — and less EUV radiation for the thermosphere to absorb means a cooler thermosphere.

The thermososphere loses its heat energy (and cools down) because carbon dioxide and nitric oxide molecules emit infrared radiation out into space and into the lower atmosphere, subsequent to collisions with oxygen atoms. The amount of infrared radiation varies with both the temperature of the thermosphere, which increases the frequency of collisions, and the amount of carbon dioxide and nitric oxide present at any given time.

Thus the amount of infrared radiation emitted by the thermosphere is a rich source of information about its energy state.

The findings show that this solar minimum is affecting the thermosphere differently than during the previous minimum. This effect, while not driving change in Earth’s weather, can make a tremendous difference to those at NASA monitoring our satellites traveling through this region: The current cold temperatures in the themosphere can help keep orbits stable.

Mlynczak serves as the associate principal investigator for SABER, which looks at infrared radiation emitted from nitric oxide and carbon dioxide in the thermosphere. Those emissions regulate the temperature and density of the thermosphere, which are driven by ultraviolet radiation and energetic particles from the Sun.

What Mlynczak and his colleagues found is that while infrared radiation levels in the thermosphere are, overall, nearly at the same levels they were nine years ago during the last solar minimum, there is a distinct difference.

Infrared radiation levels from carbon dioxide are very much in line with those observed during the last solar minimum. That much is similar. Different, though, are infrared radiation levels from nitric oxide. They’re higher than they were in 2009.

“It was just interesting to see that, so far, there’s a different aspect of this current solar minimum relative to the one in 2009,” said Mlynczak. “There’s still more geomagnetic activity going on because of the particles coming in versus the solar ultraviolet effects. We are watching closely to see how long this persists.”

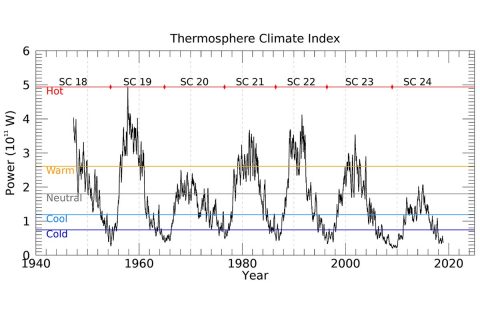

Key to the study was the Thermosphere Climate Index, or TCI, a tool Mlynczak and his colleagues developed to help monitor action in the thermosphere. The index calculates how much heat energy carbon dioxide and nitric oxide molecules in the thermosphere are radiating into space (and to the lower atmosphere).

Based on that calculation, the TCI assigns a temperature rating — Hot, Warm, Neutral, Cool or Cold. The thermosphere is currently in a Cold phase.

“What’s interesting and what’s special about the Thermosphere Climate Index is it gives us a broad measure of a terrestrial consequence due to variations in the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation or the particle precipitation,” said Mlynczak. “It’s the first such index that really has terrestrial (i.e., thermospheric) context in it.”

It also provides historical context.

“What is remarkable about the TCI is that SABER data collected over the last 17 years can be used to track the effect of the Sun on the upper atmosphere going back in time more than 70 years to 1947, covering five complete solar cycles,” said James Russell, the SABER principal investigator at Hampton University’s Center for Atmospheric Sciences in Hampton.

Scientists who would like for their satellites to stay in orbit a little longer — Mlynczak and Russell included — certainly won’t be unhappy about the TCI being Cold.

“Being in the solar minimum now is great because it means we’re going to be able to continue to operate longer without having to worry as much about the decay of the TIMED satellite orbit,” he said. “It extends our lifetime.”

But all good things must come to an end. On average, solar cycles last around 11 years. We’re likely on the tail end of the current cycle, after which solar activity will begin picking up and the thermosphere will warm and expand. The TCI will be tracking that closely.

That’ll make life a little more difficult for satellites again. On the plus side, it’ll also hasten the demise of some of the space junk that’s cluttering up low-Earth orbit. You have to take the big-picture view.

“The current cold conditions in the thermosphere are not a permanent thing,” said Mlynczak. “It’s cyclical.”